Back to Journals » Nursing: Research and Reviews » Volume 14

Ozanimod: A Practical Review for Nurses and Advanced Practice Providers

Received 1 July 2023

Accepted for publication 12 January 2024

Published 2 February 2024 Volume 2024:14 Pages 15—31

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NRR.S427698

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Pariya Fazeli

Michele Rubin,1 Christen Kutz2

1Department of Colorectal Surgery, University of Chicago IBD Center, Joliet, IL, USA; 2Colorado Springs Neurological Associates, Colorado Springs, CO, USA

Correspondence: Michele Rubin, Associate Director of IBD Center, University of Chicago IBD Center, 2914 Hintze Court, Joliet, IL, 60435, USA, Tel +1-815-347-8307, Fax +1-773-834-1995, Email [email protected]

Abstract: Ozanimod is the first sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator approved for the treatment of moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC). In clinical trials, participants with moderately to severely active UC who received once-daily oral ozanimod demonstrated significantly improved rates of clinical, endoscopic, and histologic outcomes than participants receiving placebo. Ozanimod is also approved for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS). This review summarizes safety data from UC and MS clinical trials and discusses treatment considerations when using ozanimod in clinical practice. Ozanimod is an oral, small molecule agent with a novel mechaism of action that differentiates it from other UC therapies. Ozanimod was generally well tolerated in clinical trials, and the incidence of adverse events of special interest based on prior associations with S1P receptor modulation was low overall. Of note, the risk for clinically significant bradycardia upon treatment initiation was mitigated by gradual dose titration, few patients experienced lymphopenia or serious infections, macular edema and malignancy occurred infrequently, and most hepatic events were transient and did not require treatment discontinuation. Given the safety and efficacy profile of ozanimod, it may be an early treatment option in patients with moderate disease or in those hesitant to use biologics, and it could also be beneficial after other treatments have failed. Further investigation is needed to determine the positioning of ozanimod within the UC treatment armamentarium.

Plain Language Summary: This article provides information about the use of ozanimod in treating patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC) and offers practical guidance for nurses, nurse practitioners, and other healthcare providers to help address questions that may come up in clinical practice. Ozanimod is an oral medication that improves UC symptoms as well as current biologics, while also reducing the need for corticosteroids, a key aspect in treating UC. Ozanimod may be used either after a patient has failed a biologic or as an early treatment option before starting a biologic in patients with moderate UC who may be hesitant to start biologics. This article includes tools to help guide clinical practice decision-making, educate on possible adverse events, and provide the monitoring necessary to ensure patient safety and best practices in the use of ozanimod.

Keywords: ulcerative colitis, ozanimod, sphingosine 1-phosphate, safety

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an inflammatory disease characterized by diffuse inflammation in the colon and rectum.1 Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) signaling plays an essential role in lymphocyte trafficking and inflammation.2,3 S1P molecules bind to S1P1 receptors on lymphocytes, and this enables the lymphocytes to migrate from lymphoid tissues into the circulation and to sites of inflammation.2–4 In UC, increased S1P levels in inflamed gut tissue recruit immune cells and mediators of inflammation.2–4 Ozanimod is an S1P receptor modulator that binds with high affinity to the S1P1 and S1P5 receptors.5 Ozanimod binding leads to internalization of S1P1 receptors, thereby inhibiting detection of S1P and limiting the ability of lymphocytes to egress from lymphoid tissue into circulation (Figure 1).5 Although the mechanism by which ozanimod exerts its therapeutic effects in UC is unknown, it may involve the reduction of lymphocyte migration into the intestine.6

|

Figure 1 Potential mechanism of action of ozanimod in inflammatory bowel disease. Binding of ozanimod induces S1P1 receptor internalization, blocking the capacity of lymphocytes to egress from lymphoid tissue into circulation.5,7,8 The mechanism by which ozanimod exerts therapeutic effects in inflammatory bowel disease is unknown but may involve the reduction of lymphocyte migration into, or direct effects on, the gut.5 Although S1P is prominent throughout the bloodstream, it is not depicted in the bloodstream on the left for simplicity in this conceptual illustration. aIncluding T cells and B cells. bInnate immune cells, which are responsible for antigen presentation and immunosurveillance, include macrophages, monocytes, and natural killer cells, among others. Adapted from Sands BE, Schreiber S, Blumenstein I, Chiorean MV, Ungaro RC, Rubin DT. Clinician’s guide to using ozanimod for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;jjad112. Creative Commons.9 Abbreviation: S1P, sphingosine 1-phosphate. |

Ozanimod is the first approved S1P receptor modulator for the treatment of moderately to severely active UC in the United States and European Union. Ozanimod is also approved in multiple countries for the treatment of relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease characterized by lesions of the central nervous system,10 including clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease in the United States and relapsing-remitting disease in the European Union and Canada.1,6,11,12 Ozanimod is a small molecule therapy that can be administered orally because its low molecular weight allows it to be absorbed through the lining of the small intestine and rapidly enter the bloodstream.13 This is in contrast to biologic therapies, which are large macromolecular structures composed of complex polypeptide chains that require parenteral (intravenous or subcutaneous) administration.13

In phase 2 and 3 clinical trials, once-daily oral ozanimod 0.92 mg (equivalent to ozanimod HCl 1 mg) was significantly more effective than placebo in improving rates of clinical, endoscopic, and histologic outcomes in adult patients with moderately to severely active UC on concomitant oral aminosalicylates and/or corticosteroids with or without prior biologic exposure.14,15 Efficacy was demonstrated during initial treatment for inducing a response to treatment (ie, induction therapy) and with continued treatment for maintaining a response (ie, maintenance therapy). TOUCHSTONE (NCT01647516) was a 32-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of ozanimod induction and maintenance therapy in UC.14 At Week 8 of the induction period, clinical remission (defined as Mayo score ≤2, with no subscore >1) occurred in significantly more patients who received ozanimod (11/67; 16%) than placebo (4/65; 6%; P = 0.048). With 24 weeks of continued maintenance therapy, the percentage of patients with clinical remission increased to 21% (14/67) with ozanimod, which was significantly greater than placebo (4/65; 6%; P = 0.01).

The phase 3 trial in UC was True North (NCT02435992), a 52-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind study that further examined induction and maintenance therapy with ozanimod versus placebo.15 After 10 weeks of double-blind induction therapy, clinical remission (defined as rectal bleeding subscore = 0, stool frequency subscore ≤1 [with a decrease of ≥1 point from baseline], and endoscopy subscore ≤1) was achieved by significantly more patients who received ozanimod (79/429; 18.4%) than placebo (13/216; 6.0%; P < 0.001). After induction, patients who responded to ozanimod therapy were randomly assigned to either continue ozanimod or switch to placebo for a subsequent 42-week maintenance period. At the end of maintenance, clinical remission was achieved by significantly more patients who continued ozanimod (85/230; 37.0%) than received placebo (42/227; 18.5%; P < 0.001). Significant improvements were also observed with ozanimod compared with placebo for clinical response, endoscopic improvement, and mucosal healing at the end of the induction and maintenance periods; corticosteroid-free remission was superior for ozanimod compared with placebo at the end of maintenance. In addition, patients receiving ozanimod demonstrated decreases in rectal bleeding and stool frequency by Week 2 of treatment.

The long-term efficacy of ozanimod 0.92 mg in UC is being assessed in the True North open-label extension (OLE) study. The True North OLE is ongoing and includes patients who remained in an extension study from TOUCHSTONE at study closure and patients from True North who did not respond during the induction period, relapsed during the maintenance period, or completed maintenance treatment.15,16 An interim analysis of the OLE demonstrated that patients who maintained clinical response after 1 year of ozanimod treatment in True North sustained symptomatic, clinical, endoscopic, and histologic efficacy for 2 additional years of treatment during the OLE.17

Ozanimod was also efficacious in two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, active-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trials in patients with relapsing MS.18,19 Adjusted annualized relapse rate (based on relapses defined as new or worsening neurological symptoms attributable to MS persisting for >24 hr that were preceded by stable or improving neurological state for ≥30 days, and confirmed if accompanied by objective neurological worsening per the Expanded Disability Status Scale) was significantly lower in patients treated with once-daily oral ozanimod 0.92 mg for ≥12 months in the SUNBEAM trial (NCT02294058) and 24 months in the RADIANCE trial (NCT02047734) compared with patients treated with once-weekly intramuscular interferon beta-1a 30 µg. Ozanimod was also associated with lower numbers of new or enlarging lesions and reduced brain volume loss compared with interferon beta-1a. With long-term treatment of up to 8 continuous years in a subsequent OLE (DAYBREAK; NCT02576717), the adjusted annualized relapse rate was 0.103, with 71% of patients remaining relapse-free during the first 48 months, and numbers of new or enlarging lesions were low.20

Overall, the phase 3 clinical trials demonstrated the efficacy of ozanimod therapy for up to 1 year in patients with moderately to severely active UC and for up to 2 years in patients with relapsing MS,15,18,19 with long-term durability demonstrated in the OLE studies for up to 3 years in UC and 8 years in MS.17,20 In March 2020, ozanimod 0.92 mg was approved in the United States for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS based on data from the phase 3 SUNBEAM and RADIANCE trials; in May 2021 ozanimod 0.92 mg received US approval for the treatment of moderately to severely active UC based on results from the phase 3 True North study.6 This review describes safety data from the ozanimod phase 2 and 3 clinical trials and outlines strategies for the initiation of ozanimod and for the identification and management of adverse events (AEs) that may occur with ozanimod treatment in clinical practice. This review also provides insight on the potential placement of ozanimod in the UC treatment armamentarium.

Overall Safety Findings in UC Trials

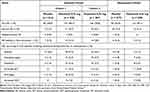

Overall safety of ozanimod in the treatment of UC has been reported from 132 patients on ozanimod 0.92 mg or placebo in the phase 2 TOUCHSTONE study, 1012 patients (ozanimod 0.92 mg or placebo) in the induction period of the phase 3 True North study, and 457 patients (ozanimod 0.92 mg or placebo) in the maintenance period of True North.14,15 Descriptive summaries of AE data from these studies are shown in Table 1 (True North) and Supplementary Table 1 (TOUCHSTONE); no statistical comparisons between ozanimod and placebo were performed.

|

Table 1 Adverse Events in Patients with UC in the Phase 3 True North study15 |

In the TOUCHSTONE study, no substantial differences were reported between treatment groups in the incidence of overall AEs (Supplementary Table 1).14 Serious AEs (defined as AEs that resulted in death, were life-threatening, required inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity, or were congenital abnormalities/birth defects) occurred more frequently with placebo (9%) than ozanimod 0.92 mg (4%). AEs leading to treatment discontinuation also occurred more frequently with placebo (6%) than ozanimod 0.92 mg (1%). In the True North study, the overall incidence of AEs was similar between patients who received placebo and ozanimod (38% vs 40%) during the induction period and was higher with patients who received ozanimod during the maintenance period (37% vs 49%) (Table 1).15 The occurrence of serious AEs and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation was not substantially different between patients who received ozanimod or placebo. The most commonly occurring AEs with ozanimod in these clinical trials were anemia (0–4.4%), nasopharyngitis (0–3.5%), UC flare (4%; reported for TOUCHSTONE only), pyrexia (4%; reported for TOUCHSTONE only), headache (2.7%–3.5%), and increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT; 1.6%–4.8%).14,15

Adverse Events of Special Interest (AESIs) in UC and MS Trials

A number of AESIs based on prior associations with S1P receptor modulation have been analyzed in patients with UC who received double-blind ozanimod 0.92 mg in the pooled TOUCHSTONE14 and True North15 induction studies (n = 496) and in the True North maintenance study (n = 230), as well as in patients with MS who received double-blind ozanimod 0.92 mg in the pooled phase 3 SUNBEAM and RADIANCE studies (n = 882).6,18,19 Table 2 summarizes the incidence of key AESIs that occurred with ozanimod in UC and MS studies; MS data are included along with UC data to strengthen the knowledge of the overall safety profile of ozanimod.

|

Table 2 Incidence of Adverse Events of Special Interest in Patients with UC and MS Treated with Ozanimod 0.92 mg6,15 |

Cardiovascular Events

Initiation of S1P receptor modulators may result in a temporary decrease in heart rate or temporary atrioventricular conduction delays (limited to the first dose), which are mediated via S1P1 and S1P3 receptor binding in the heart.21–23 However, this effect can be mitigated with gradual dose titration of ozanimod.21,23 Thus, a 7-day dose titration regimen is recommended upon ozanimod initiation to reduce the risk of cardiac AEs as follows: ozanimod 0.23 mg (equivalent to ozanimod HCl 0.25 mg) once daily on days 1–4, ozanimod 0.46 mg (equivalent to ozanimod HCl 0.5 mg) once daily on days 5–7, and ozanimod 0.92 mg once daily starting on day 8 and thereafter.6,11,12

After the initial dose of ozanimod 0.23 mg on day 1 of the pooled UC induction studies and pooled MS studies, the greatest mean decrease from baseline in heart rate occurred at hour 5 (UC, 0.7 bpm; MS, 1.2 bpm) but returned to near baseline at hour 6.6 In those studies, bradycardia was reported on or after day 1 in fewer than 1% of patients who received ozanimod (Table 2).6 No instances of bradycardia were reported in the True North maintenance study.6,15 Mobitz type II second- or third-degree atrioventricular block was not reported with ozanimod in the pooled UC induction studies or the pooled MS studies with dose titration.6

In addition to heart rate, blood pressure was also monitored in clinical trials. The mean increase in systolic blood pressure (SBP) from baseline in the pooled UC induction studies was 3.7 mm Hg in ozanimod-treated patients and 2.3 mm Hg in placebo-treated patients; the mean increase from baseline in SBP was 5.1 mm Hg in ozanimod-treated patients and 1.5 mm Hg in placebo-treated patients in the True North maintenance period.6 Blood pressure changes were similar in the pooled MS studies, with a mean increase in SBP of approximately 1–2 mm Hg over those on interferon beta-1a.6 Hypertension was reported as an AE in 1%–4% of patients who received ozanimod compared with none with placebo (Table 2); hypertensive crisis was reported in two patients who received ozanimod and one patient who received placebo in the UC studies and in two patients who received ozanimod in the MS studies.6

Lymphocyte Counts and Infections

Reductions in peripheral blood lymphocyte counts to approximately 45% of baseline were observed after 3 months of ozanimod treatment in controlled UC and MS studies, which is expected based on the mechanism of action (MOA) of ozanimod.6 Findings from True North demonstrated that patients with UC who continuously received ozanimod over 52 weeks had reductions in absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) that were sustained over time, and in patients who were switched from ozanimod to placebo, mean ALC levels began to recover within 8 weeks of discontinuation (Figure 2).24 Overall in the UC and MS clinical trials, approximately 2%–3% of patients treated with ozanimod had lymphocyte counts <0.2 x 109/L (Table 2), although lymphocyte counts generally returned to >0.2 x 109/L with continued treatment.6 After discontinuing ozanimod, the median time for lymphocyte counts to return to their normal range was 30 days; approximately 80%–90% of patients with UC or MS were within the normal range within 3 months of ozanimod discontinuation.6

|

Figure 2 Mean ALC over time in the induction and maintenance periods of the True North study in patients with UC.24 Patients who received continuous placebo (placebo) had stable levels of mean ALC over time, remaining within the normal range (1.02–3.36 × 109/L). Patients who continuously received ozanimod during the induction and maintenance periods (ozanimod/ozanimod) had sustained ALC reductions over time, which began to recover within 8 weeks in patients who discontinued ozanimod during the maintenance period (ozanimod/placebo). Error bars denote standard error. Reprinted from Sands BE, Schreiber S, Blumenstein I, Chiorean MV, Ungaro RC, Rubin DT. Clinician’s guide to using ozanimod for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;jjad112. Creative Commons.9 Abbreviations: ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; UC, ulcerative colitis. |

The risk of infection may be increased while on ozanimod due to reduced circulating lymphocytes. Some of the infections could be serious in nature.6 In UC and MS clinical studies, infections were reported in 10%–35% of patients receiving ozanimod and in 11%–12% of patients receiving placebo; infections considered serious AEs occurred in ≤1% of patients receiving ozanimod and in 0.4%–1.8% of patients receiving placebo (Table 2).6

Herpes simplex encephalitis and varicella zoster meningitis have occurred with S1P receptor modulators.6 Herpes zoster was reported as an adverse reaction in 0.4%–2.2% of patients receiving ozanimod in the UC and MS studies; no infections were serious or disseminated in the UC studies.6 Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) has also occurred with S1P receptor modulators.6 PML is a rare neurological disorder that typically presents in immunocompromised patients.6 It is caused by demyelination of white matter in the brain and usually results in severe disability or death.6,25 To date, no cases of PML have been reported in the UC studies, although one case was reported in a patient with MS who received ozanimod for approximately 4 years; the patient discontinued ozanimod and the outcome was nonfatal with neurologic sequelae.20

Macular Edema

S1P receptor modulators have been associated with an increased risk of macular edema, particularly in patients with preexisting risk factors or comorbidities (uveitis and diabetes).6 Macular edema was reported in fewer than 1% of patients treated with ozanimod (Table 2) and in no patients who received placebo in the UC and MS studies.6

Liver Enzyme Levels and Liver Injury

Elevations of liver enzymes may occur with ozanimod treatment.6 In the True North double-blind induction and maintenance studies and pooled MS studies, ALT elevations ≥3 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) occurred in approximately 3%–6% of patients who received ozanimod and in fewer than 1% of patients who received placebo; ALT elevations to ≥5 times the ULN occurred in approximately 1%–2% of patients who received ozanimod (Table 2).6,15 In all controlled and uncontrolled UC studies and pooled MS studies, 96% and 79% of patients, respectively, with ALT ≥3 times the ULN had their ALT return to <3 times the ULN within approximately 2–4 weeks while continuing ozanimod.6 Treatment discontinuation rates because of elevations in liver enzymes were low: 0.4% in controlled UC studies and 1.1% in the pooled MS studies.6

Malignancies

An increased risk of cutaneous malignancies has been observed with other S1P receptor modulators.6 In True North, no malignancies were attributed to ozanimod treatment during the induction period and two malignancies (0.9%; basal cell carcinoma and rectal adenocarcinoma) occurred while receiving double-blind ozanimod maintenance (Table 2).15 A retrospective review of the screening endoscopy for the patient with rectal adenocarcinoma indicated the presence of a mass in the same location of the mass identified during the study (end of study, following approximately 1 year of ozanimod); therefore, it does not appear that this malignancy was treatment-emergent.

In an interim analysis of the DAYBREAK OLE study of 2787 patients with MS treated with ozanimod 0.46 mg or 0.92 mg during any of the four phase 1–3 parent trials or during the OLE, treatment-emergent malignancies occurred in 1.4% of patients (13 nonmelanoma skin cancers, 1 melanoma, and 24 noncutaneous malignancies).20 A total of three deaths due to malignancies were reported, which all occurred during the OLE (metastatic pancreatic carcinoma, disseminated cancer with unknown primary, and glioblastoma).

Pulmonary/Respiratory Effects

At week 10 of the True North induction period, reductions in forced expiratory volume over 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) from baseline occurred with ozanimod (Table 2).6 Similar findings were reported in the pooled MS studies; in ozanimod-treated patients, reductions from baseline in FEV1 were observed as early as 3 months and were maintained through 12 months, and reductions from baseline in FVC were reported at month 3.6 It is unclear if FEV1 and FVC reductions are reversible after discontinuing ozanimod or if changes were progressive with continued ozanimod treatment.6

Pregnancy Outcomes

The S1P receptor has an important role in embryogenesis, including vascular and neural development, and animal studies have demonstrated adverse effects of ozanimod on the development of the fetus.6 In all controlled and uncontrolled UC and MS studies, 56 female patients became pregnant while on ozanimod, resulting in 57 outcomes (due to a twin pregnancy) that included 30 live births (1 with a congenital anomaly and 3 premature births), nine early spontaneous losses, and 12 elective terminations; 4 pregnancies were ongoing at data cutoff and 2 pregnancies had no information (Supplementary Table 2).26,27 All ozanimod pregnancy exposures occurred during the first trimester.26,27 The incidence of spontaneous abortion was 16%,26,27 similar to the expected incidence in the general population (12%–22%).28,29 The incidence of preterm birth (5.4% of live births)26,27 was lower than in the global population (10.6%; uncertainty interval, 9.0–12.0).30

Ozanimod Use in Clinical Practice for the Treatment of UC

The safety profile of ozanimod as observed in UC and MS clinical trials has informed recommendations for the use of ozanimod, as detailed in the US prescribing information.6 Here we discuss guidance for determining patient suitability for ozanimod treatment, monitoring AEs and efficacy during treatment, and interrupting or discontinuing ozanimod, as well as potential drug/food interactions. We also summarize safety data regarding specific AESIs that have been identified based on prior associations with S1P receptor modulation. In addition, a checklist to use before and during ozanimod treatment is provided in Table 3.

|

Table 3 Checklist for Ozanimod Treatment in Patients with UC |

Assessments and Considerations Prior to Initiating Ozanimod

Ozanimod is indicated for adults with moderately to severely active UC. It is contraindicated in patients who have experienced a myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stroke, transient ischemic attack, decompensated heart failure requiring hospitalization, or New York Heart Association class III/IV heart failure in the last 6 months; have the presence of Mobitz type II second- or third-degree atrioventricular block, sick sinus syndrome, or sinoatrial block, unless the patient has a functioning pacemaker; have severe untreated sleep apnea; or are taking a monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitor.6 Patients with certain preexisting conditions, such as significant QT prolongation, arrhythmias, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, history of myocardial infarction, or history of second-degree atrioventricular block, may initiate ozanimod after consultation with a cardiologist.6 Ozanimod is not recommended for patients with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class C) or receiving strong CYP2C8 inhibitors or inducers.6 Figure 3 provides detailed guidance for determining patient suitability for initiating ozanimod treatment according to US prescribing information recommendations.6

|

Figure 3 Guide to establishing suitability for ozanimod treatment in patients with UC.6 Ozanimod may be suitable for adult patients with moderately to severely active UC. The ideal patient has lost response or failed to respond to conventional or advanced therapies. Patients must pass preinitiation assessments as described in the US prescribing information. Consultation with a cardiologist is recommended prior to treatment initiation in patients with preexisting cardiac conditions. Caution is advised for patients at risk for macular edema and those taking immunosuppressive drugs. The prescribing information also outlines patients for whom ozanimod is contraindicated or not recommended. This figure outlines the key issues but is not comprehensive of all considerations detailed in the prescribing information. Abbreviations: 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; AV, atrioventricular; CBC, complete blood count; ECG, electrocardiogram; HF, heart failure; JAK, Janus kinase; MAO, monoamine oxidase; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; UC, ulcerative colitis; VZV, varicella zoster virus. |

Before initiating ozanimod, a series of assessments and considerations are recommended.6 An electrocardiogram should be performed to assess for selected preexisting conduction abnormalities, and a complete blood count (with lymphocyte count) should be obtained within 6 months or after discontinuing prior therapy. Initiation of ozanimod should be delayed if a patient has an active infection. Varicella zoster virus vaccination is recommended in varicella zoster virus antibody-negative patients at least 1 month prior to initiating ozanimod. Any other live-attenuated immunizations needed should be administered at least 1 month prior to initiating ozanimod. Ophthalmic evaluation should be performed in patients with a history of macular edema or who are at high risk for macular edema (ie, patients with a history of diabetes mellitus or uveitis), and transaminase and bilirubin levels should be obtained within 6 months of treatment initiation to assess liver function. Current or prior use of certain medications, especially immunosuppressive drugs or drugs that could slow heart rate or atrioventricular conduction, should be determined.6

AE Monitoring

In addition to conventional AE monitoring, patients should be monitored for S1P-related AESIs during ozanimod treatment.6 Blood pressure should be monitored regularly during treatment6 and we recommend that antihypertensive therapy should be initiated if patients experience uncontrolled hypertension. Patients should be monitored for infections during and 3 months after treatment discontinuation, as elimination of ozanimod may take up to 3 months.6 Physicians should be vigilant for signs or symptoms of PML and cryptococcal meningitis, as cases of both have been reported with S1P receptor modulators.6 Patients who present with progressive unilateral weakness, clumsiness, vision disturbance, confusion, or personality changes should be evaluated for PML.6 Patients with signs or symptoms of intracranial pressure, unexpected neurological or psychiatric signs or symptoms, or accelerated neurological deterioration should have a complete physical and neurological examination and magnetic resonance imaging should be considered, as rare cases of posterior reversible encephalopathy have occurred with S1P modulators.6 Patients with changes in vision or symptoms of macular edema should undergo ophthalmic evaluation, and regular evaluations should be performed in patients with diabetes mellitus or history of uveitis.6 While the US prescribing information does not provide recommendations for routine monitoring of ALC or liver function, we recommend that ALC and liver enzymes should be monitored approximately every 3 months (see Table 3).9,12 Liver enzymes should also be assessed in patients who develop symptoms of hepatic dysfunction, including unexplained nausea or vomiting, abdominal pain, fatigue, anorexia, jaundice, or dark urine as recommended in the US prescribing information.6 Respiratory function should be assessed with spirometric evaluation if clinically indicated.6

Treatment Duration and Efficacy Monitoring

There is no official recommendation for length of ozanimod treatment. However, clinical trial data suggest that ozanimod can be used long-term for the treatment of UC. Findings from an interim analysis of the phase 3 True North OLE study in patients with UC demonstrated that ozanimod maintains efficacy and safety for up to 3 years of continuous treatment.17 Additionally, the efficacy and safety of ozanimod have been demonstrated for up to 8 years of continuous treatment in MS.20 Further analyses are investigating the efficacy and safety of ozanimod beyond 3 years in patients with UC.

We recommend that the efficacy of ozanimod should be evaluated regularly during treatment using a treat-to-target approach that includes symptom, biomarker, endoscopic, and histologic monitoring. Ongoing assessment of symptoms should be monitored at clinic visits 3, 6, and 12 months after initiating treatment, and then every 6 to 12 months thereafter unless there is a concern for disease flare; patients should report any changes in symptoms between visits. Based on clinical trial and real-world data, patients should expect symptomatic improvement as early as 2 weeks after initiating treatment.15,31–33 If symptoms do not improve or patients do not respond to ozanimod initially (ie, within 10 weeks), clinical trial data suggest that extended induction treatment should be considered for an additional 5–10 weeks to achieve a symptomatic response.34 Evaluation of inflammatory biomarkers (eg, C-reactive protein, fecal calprotectin) and intestinal ultrasound (IUS; a new point-of-care imaging technique that correlates with endoscopy for assessment of intestinal healing) should be performed at 3 months post-treatment initiation. Endoscopy and histology assessments or IUS should be performed at 6 and 12 months post-treatment initiation, and then every 6 to 12 months thereafter. IUS can additionally be used as a point-of-care tool during clinical visits whenever there is a need to assess whether ozanimod is effective and if intestinal healing is occurring.

Considerations for Interrupting or Discontinuing Ozanimod Treatment Related to AEs

Ozanimod treatment interruption or discontinuation should be considered if certain AEs occur during treatment.6 Treatment interruption should be considered if a patient develops a serious infection. If patients present with signs or symptoms of cryptococcal infection, treatment should be interrupted until a diagnosis has been excluded. Treatment should be interrupted if PML is suspected and discontinued if it is confirmed. If posterior reversible encephalopathy is suspected, treatment should be discontinued. It is our opinion that ozanimod can be continued during active COVID-19 infection at the provider’s discretion. While the US prescribing information does not provide guidance related to ALC, we recommend following the guidance in the European Union summary of product characteristics that a confirmed ALC of <0.2 × 109/L should lead to treatment interruption until ALC returns to >0.5 × 109/L, when ozanimod can be reinitiated.12 The potential benefits and risks of continuing ozanimod treatment should be considered in patients who develop macular edema. Treatment should be discontinued in patients who develop symptoms of hepatic dysfunction and subsequently have liver injury confirmed upon liver enzyme assessment.6 The US prescribing information also does not provide guidance related to elevated liver enzymes detected during routine monitoring in the absence of liver injury; therefore, we recommend following the guidance in the European Union summary of product characteristics that in patients with confirmed liver transaminase levels >5 times the ULN, ozanimod should be interrupted until levels normalize, at which time ozanimod can be reinitiated.12

Potential Drug or Food Interactions with Concomitant Ozanimod Treatment

Certain drugs may have clinically important interactions when used concomitantly with ozanimod.6 Advice from a cardiologist is recommended when ozanimod is considered in patients receiving class Ia or class III antiarrhythmic drugs. Ozanimod generally should not be used in patients treated with QT-prolonging drugs with known arrhythmogenic properties. Coadministration of ozanimod in combination with a beta blocker and calcium channel blocker is not recommended, as additive effects on heart rate may occur; if concurrent treatment is considered, advice from a cardiologist is recommended.6

An active metabolite of ozanimod has been shown to inhibit MAO type B in vitro.6 Because MAO inhibitors can lead to elevation of the neurotransmitters serotonin and/or norepinephrine in the central nervous system,35 serious adverse reactions, including hypertensive crisis, may occur with coadministration of ozanimod and MAO inhibitors or medications that increase these neurotransmitters, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).6 MAO inhibitors are contraindicated with ozanimod coadministration and initiation should be delayed until at least 14 days after ozanimod discontinuation.6 Patients with inflammatory bowel diseases often have comorbid mental health disorders, including anxiety and depression, and may receive treatment with SSRIs and SNRIs36; mental health assessments may be useful when considering potential treatments. Coadministration with SSRIs or SNRIs is not recommended with ozanimod6; however, post hoc analyses of MS and UC studies found no reports of serotonin syndrome, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, or malignant hyperthermia in those treated concurrently with an SSRI or SNRI and ozanimod.37 Patients should be monitored for hypertension if concomitant use with drugs that increase norepinephrine or serotonin does occur. Severe hypertension may also occur if tyramine is absorbed intact while on ozanimod, so patients should avoid foods with very high amounts of tyramine (ie, more than 150 mg), including aged, fermented, cured, smoked, and pickled foods (eg, aged cheese, pickled herring).6

Caution should be used in patients with a history of antineoplastic, immune-modulating, or immunosuppressive therapies due to the risk of additive effects; the half-lives and MOAs of these treatments should be considered to avoid additive effects.6 Live attenuated vaccines should be avoided during and for up to 3 months after treatment with ozanimod, as vaccinations may be less effective when administered concurrently or before ozanimod is eliminated.6

CYP2C8 inhibitors may increase exposure to the active metabolites of ozanimod, potentially increasing the risk of AEs, and CYP2C8 inducers may reduce exposure to active metabolites of ozanimod, potentially decreasing ozanimod efficacy.6 Therefore, coadministration with strong CYP2C8 inhibitors and inducers is not recommended.6

Use of Ozanimod in Specific Populations

There are some additional considerations to take into account with ozanimod use in specific populations.6 Adequate and well-controlled studies of ozanimod use in pregnant women are lacking, but S1P has been shown to be involved in embryogenesis. Therefore, women of childbearing potential should use effective contraception during ozanimod treatment and for 3 months after its discontinuation. There are no data available regarding human lactation, but ozanimod and ozanimod metabolites were detected in lactation in animal studies. The safety and efficacy of ozanimod have not been investigated in pediatric patients, and clinical trials did not include enough patients aged ≥65 years to determine if ozanimod response differs in the older population. Although steady-state exposure of an ozanimod metabolite in patients with UC aged >65 years was 3%–4% greater than in patients aged 45–65 years and 27% greater than in patients aged <45 years, no meaningful differences in pharmacokinetics were observed based on age. In patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment (Child–Pugh class A or B), exposures to ozanimod and its metabolites were higher compared with healthy participants, which may increase the risk of AEs. These patients should be titrated using the same dosing schedule as all other patients, but they should take ozanimod 0.92 mg every other day starting on Day 8 after completing the titration pack. However, the effects of severe hepatic impairment (Child–Pugh class C) on ozanimod pharmacokinetics are unknown, so ozanimod use in these patients is not recommended. Although pharmacokinetic analyses showed that steady-state exposure of an ozanimod metabolite was approximately 50% lower in smokers compared with nonsmokers, no meaningful difference in ALC or impact on efficacy was observed. No clinically significant differences in ozanimod pharmacokinetics were observed based on sex or weight, in patients with renal impairment, or in Japanese or White clinical trial participants.6

Use of Ozanimod with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Vaccinations

Some immunomodulators and biologics have been shown to attenuate SARS-CoV-2 vaccine response.38,39 An analysis from the DAYBREAK OLE study demonstrated that participants with MS who received ozanimod developed serologic response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, regardless of demographic characteristics and absolute lymphocyte count at the time of vaccination.40 Of the total 109 participants with no previous SARS-CoV-2 exposure, seroconversion occurred in 100% (80/80) and 62% (18/29) of fully vaccinated mRNA and non-mRNA vaccine recipients, respectively. Some participants developed low receptor binding domain (RBD) antibody levels and may benefit from booster doses as antibody levels increased after the second dose with mRNA vaccine recipients. In participants with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 exposure, seroconversion occurred in 100% (39/39) of both mRNA and non-mRNA vaccine recipients and RBD antibody levels were higher than in those without SARS-CoV-2 exposure, suggesting a primed immune response.

Placement of Ozanimod in the UC Treatment Paradigms

Ozanimod is unique compared with other currently available UC therapies in several ways. First, ozanimod, which has a novel MOA compared with other UC therapies, is the first S1P receptor modulator approved for the treatment of moderately to severely active UC.1,6,9 Second, small molecule therapies have a decreased risk for immunogenicity compared to large molecule biologics; the immunogenicity occurring with biologics, such as anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, may lead to loss of response.13,41 The decreased risk for immunogenicity with small molecule therapies, such as ozanimod, may be advantageous for sustained efficacy.13 Third, the oral route of administration may be preferred and perceived as more convenient by some patients.13,42,43 Finally, ozanimod, like other oral therapies (eg, Janus kinase [JAK] inhibitor tofacitinib),44,45 has shown a rapid onset of action in patients with UC, with improvements in rectal bleeding and stool frequency within 2 weeks (1 week after reaching the recommended dose of 0.92 mg with dose titration) compared with placebo in the True North study.15 Some newer biologics, such as vedolizumab, have a slower onset, with peak effect not expected until 10–14 weeks.46

There is no official guidance on the placement of ozanimod in the treatment of UC.1 There are, however, some characteristics of ozanimod that may be considered. The US prescribing information does not require failure of conventional UC therapies, nor does it require treatment with an anti-TNF agent prior to initiating ozanimod.6 Therefore, in our opinion, ozanimod could be positioned either after the first course of corticosteroids or after failure or loss of response to other conventional therapies (ie, 5-aminosalicylic acid and immunomodulators) or advanced therapies (ie, biologics [including anti-TNF agents] and JAK inhibitors) (Figure 3), and may be most efficacious before patients progress to biologics.

Given findings from a recent systematic review that showed approximately 40% of patients with UC relapsed within 6–12 months and 48% relapsed within 6–18 months of initiating 5-aminosalicylic acid treatment,47 ozanimod may be considered as second line of treatment after 5-aminosalicylic acid but before corticosteroids. However, even though the FDA approval of ozanimod does not require a course of corticosteroids after initial treatment failure, insurers or other payors may still have such requirements. Ozanimod efficacy in patients with UC is comparable to some biologics,1,48 but patients who had prior exposure to anti-TNF agents may take longer to respond to treatment.15 In the phase 3 True North study, patients with prior exposure to TNF inhibitors did not achieve statistically significant improvements compared with placebo after the initial 10-weeks of ozanimod induction, but did have statistically significant improvements compared with placebo with longer-term maintenance therapy.15 This suggests that ozanimod could be initiated before biologics, especially in patients who have moderate disease, prefer an oral therapy, or are hesitant to start a biologic due to the perception that injected or infused therapies are associated with more AEs. Ozanimod may be a first choice for patients with concurrent MS, as ozanimod is also indicated for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS.6,11,12

Ozanimod may have certain safety advantages over other UC therapies. Because ozanimod is given orally, there is no risk of the infusion- or injection-related AEs that have been reported with some biologics (eg, adalimumab, ustekinumab).49,50 The prescribing information for ozanimod does not currently carry any boxed warnings,6 whereas the prescribing information for tofacitinib and some biologics (eg, adalimumab, infliximab) carry boxed warnings about the risk of serious infections.51–53 There may be less risk of infection with ozanimod, as it only inhibits subsets of immune cells from entering circulation and does not downregulate overall immune function.7,13,54 In addition, the rates of serious infections were low and similar between patients treated with ozanimod and placebo in the True North study.15 The prescribing information for tofacitinib also carries a boxed warning for major cardiovascular AEs (ie, cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke) and thrombosis.51 The ozanimod prescribing information does not report similar cardiovascular risks in clinical trials.6

Certain situations may lead a patient with UC to consider switching to ozanimod from another therapy (Supplementary Table 3). Ozanimod may be an optimal choice for a patient who loses response to other therapies, is unable to tolerate infusion or injection of a biologic, has an aversion to needles, or is concerned about risk of AEs associated with JAK inhibitors. A patient experiencing anti-TNF–induced lupoid reaction or anti-TNF–induced psoriasis or palmoplantar pustulosis may consider switching to ozanimod therapy.

Summary and Conclusions

Ozanimod is a novel agent approved for use in adults with moderately to severely active UC.6,12 It is an oral, once-daily therapy not requiring infusion or injection.5,6 This review provides an overview of ozanimod safety data from clinical trials and offers practical considerations for using ozanimod in clinical practice. The efficacy data of ozanimod in UC have suggested that ozanimod has similar efficacy to existing biologics,1,48 while also offering corticosteroid-sparing effects and a rapid onset of action.15 Ozanimod was generally well tolerated in clinical trials. The most commonly reported AEs in ozanimod-treated patients with UC included headache, anemia, nasopharyngitis, arthralgia, and increased liver enzymes.14–16 The incidences of serious AEs and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation with ozanimod were low and similar to those observed with placebo.14–16

The incidences of AESIs, which were identified based on prior associations with S1P receptor modulation, were generally low with ozanimod in UC and MS clinical trials6 and informed the guidance on initiating ozanimod and monitoring during and after treatment. When initiating ozanimod, first-dose cardiac AEs are mitigated by using gradual dose titration21,23; in clinical trials using this approach, the incidences of cardiovascular AEs were low.6 An electrocardiogram is encouraged before ozanimod initiation to identify preexisting cardiac conditions. Ozanimod is contraindicated in patients with certain current or recent cardiac conditions, and consultation with a cardiologist is recommended for patients with other current or past cardiac conditions.6 First-dose cardiac monitoring is not required with ozanimod in the United States.6 While decreases in peripheral blood lymphocyte count are an expected pharmacodynamic effect of ozanimod, few patients in clinical trials of ozanimod experienced lymphopenia, lymphocyte counts recovered upon treatment discontinuation, and the incidence of serious infections was low.6 Ozanimod initiation should, however, be delayed in patients with an active infection.6 Rates of macular edema were low, but patients with diabetes mellitus or a history of uveitis should be evaluated prior to initiation of ozanimod and regularly during treatment.6 Most hepatic events were transient and resolved while continuing treatment and did not result in treatment discontinuation, but ozanimod use in patients with severe hepatic impairment is not recommended.6 In addition, certain medications and foods should be avoided or use monitored with concomitant ozanimod use.6 Finally, the safety and efficacy of ozanimod has not been adequately investigated in specific populations, including pregnant women, pediatric and geriatric populations, and patients with severe hepatic impairment.6 This warrants future investigations of ozanimod in these specific groups of patients.

Because it is an oral small molecule with a novel MOA, ozanimod is differentiated from other currently available therapies for UC. Guidelines have not yet been established for ozanimod use, but, in our opinion, ozanimod could be initiated prior to biologics in certain patients, and may be best used as an early treatment option in patients with moderate disease and in those who are hesitant to start biologics. Ozanimod could also be utilized after other UC therapies with different mechanisms of action have failed. Further investigation, including head-to-head studies with other UC therapies, is needed to establish guidance for the placement of ozanimod use within the UC treatment landscape. The potential benefits of ozanimod, including efficacy, tolerability, and lack of monitoring requirements outside of usual care, should be considered when making informed treatment decisions for patients with moderately to severely active UC.

Abbreviations

AE, adverse event; AESI, adverse event of special interest; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; FEV1, forced expiratory volume over 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; MAO, monoamine oxidase; MOA, mechanism of action; MS, multiple sclerosis; OLE, open-label extension; PML, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy; S1P, sphingosine 1-phosphate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SNRI, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; UC, ulcerative colitis; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

This article is a review of safety data from previously conducted clinical trials. Therefore, we were not required to obtain ethics approval and informed consent.

Consent for Publication

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

Support for third-party writing assistance for this manuscript was provided by Alexandra Stafford, PhD, and Traci Stuve, MA, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb.

Funding

This review was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ, USA.

Disclosure

Michele Rubin: None

Christen Kutz: Speaker bureau: Biogen and Teva.

References

1. Choi D, Stewart AP, Bhat S. Ozanimod: a first-in-class sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Ann Pharmacother. 2022;56(5):592–599.

2. Aoki M, Aoki H, Ramanathan R, Hait NC, Takabe K. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling in immune cells and inflammation: roles and therapeutic potential. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:8606878.

3. Danese S, Furfaro F, Vetrano S. Targeting S1P in inflammatory bowel disease: new avenues for modulating intestinal leukocyte migration. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(suppl_2):56.

4. Schwab SR, Cyster JG. Finding a way out: lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(12):1295–1301.

5. Scott FL, Clemons B, Brooks J, et al. Ozanimod (RPC1063) is a potent sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1 (S1P1) and receptor-5 (S1P5) agonist with autoimmune disease-modifying activity. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173(11):1778–1792.

6. Bristol Myers Squibb. Zeposia [Package Insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol Myers Squibb; 2023.

7. Harris S, Tran JQ, Southworth H, Spencer CM, Cree BAC, Zamvil SS. Effect of the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator ozanimod on leukocyte subtypes in relapsing MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7:e839.

8. Selkirk JV, Yan G, Ching N, Paget K, Brand M, Hargreaves R In vitro assessment of the binding and functional responses of ozanimod and its circulating metabolites across human sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors [poster].

9. Sands BE, Schreiber S, Blumenstein I, Chiorean MV, Ungaro RC, Rubin DT. Clinician’s guide to using ozanimod for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;jjad112.

10. Ghasemi N, Razavi S, Nikzad E. Multiple sclerosis: pathogenesis, symptoms, diagnoses and cell-based therapy. Cell J. 2017;19(1):1–10.

11. Celgene Corporation. Zeposia [Product Monograph]. Mississauga, ON, Canada: Celgene Inc.; 2020.

12. Celgene Distribution B.V. Zeposia [Summary of Product Characteristics]. Utrecht, Netherlands: Celgene Distribution B.V.; 2023.

13. Olivera P, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Next generation of small molecules in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2017;66(2):199–209.

14. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Wolf DC, et al. Ozanimod induction and maintenance treatment for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(18):1754–1762.

15. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, D’Haens G, et al. Ozanimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(14):1280–1291.

16. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Hanauer S, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of ozanimod in moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results from the open-label extension of the randomized, phase 2 TOUCHSTONE study. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(7):1120–1129.

17. Danese S, Panaccione R, Abreu MT, et al. Efficacy and safety of approximately 3 years of continuous ozanimod in moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: interim analysis of the True North open-label extension. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;jjad146.

18. Cohen JA, Comi G, Selmaj KW, et al. Safety and efficacy of ozanimod versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis (RADIANCE): a multicentre, randomised, 24-month, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(11):1021–1033.

19. Comi G, Kappos L, Selmaj KW, et al. Safety and efficacy of ozanimod versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis (SUNBEAM): a multicentre, randomised, minimum 12-month, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(11):1009–1020.

20. Cree BA, Selmaj KW, Steinman L, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of ozanimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis: up to 5 years of follow-up in the DAYBREAK open-label extension trial. Mult Scler. 2022;28(12):1944–1962.

21. Chun J, Giovannoni G, Hunter SF. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator therapy for multiple sclerosis: differential downstream receptor signalling and clinical profile effects. Drugs. 2021;81(2):207–231.

22. Schmouder R, Serra D, Wang Y, et al. FTY720: placebo-controlled study of the effect on cardiac rate and rhythm in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46(8):895–904.

23. Tran JQ, Hartung JP, Peach RJ, et al. Results from the first-in-human study with ozanimod, a novel, selective sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator. J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;57(8):988–996.

24. D’Haens G, Irving P, Colombel J-F, et al. Effect of ozanimod treatment and discontinuation on absolute lymphocyte count in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results from a phase 3 randomized trial [abstract P0386]. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2021;9(S8):5.

25. Bauer J, Gold R, Adams O, Lassmann H. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130(6):751–764.

26. Afsari S, Henry A, Comi G, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in the ozanimod clinical development program in relapsing multiple sclerosis, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease [poster].

27. Dubinsky MC, Mahadevan U, Charles L, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in the ozanimod clinical development program in relapsing multiple sclerosis, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease [abstract DOP53]. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(Supplement_1).

28. García-Enguídanos A, Calle ME, Valero J, Luna S, Domínguez-Rojas V. Risk factors in miscarriage: a review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;102(2):111–119.

29. Rossen LM, Ahrens KA, Branum AM. Trends in risk of pregnancy loss among US women, 1990-2011. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2018;32(1):19–29.

30. Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(1):e37–e46.

31. Cohen NA, Choi D, Choden T, Cleveland NK, Cohen RD, Rubin DT. Ozanimod in the treatment of ulcerative colitis: initial real-world data from a large tertiary center. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(9):2407–2409.e2402.

32. Osterman MT, Longman R, Sninsky C, et al. Rapid induction effects of ozanimod on clinical symptoms and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with moderately to severely acute ulcerative colitis: results from the induction phase of True North [abstract 460]. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6 suppl):78.

33. Siegmund B, Axelrad J, Pondel M, et al. Rapidity of ozanimod-induced symptomatic response and remission in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results from the induction period of True North [abstract DOP43]. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16(suppl 1).

34. Panaccione R, Afzali A, Hudesman D, et al. Extended therapy with ozanimod for delayed responders to ozanimod in moderately to severely acute ulcerative colitis: data from the True North open-label extension study [abstract Tu1450]. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(7 suppl).

35. Baldo BA, Rose MA. The anaesthetist, opioid analgesic drugs, and serotonin toxicity: a mechanistic and clinical review. Br J Anaesth. 2020;124(1):44–62.

36. Hu S, Chen Y, Chen Y, Wang C. Depression and anxiety disorders in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:714057.

37. Colombel J-F, Charles L, Petersen A, et al. Safety of concurrent administration of ozanimod and serotonergic antidepressants in patients with ulcerative colitis [abstract PO441]. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2021;9(S8).

38. Iancovici L, Khateeb D, Harel O, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with Janus kinase inhibitors show reduced humoral immune responses following BNT162b2 vaccination. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;61(8):3439–3447.

39. Edelman-Klapper H, Zittan E, Bar-Gil Shitrit A, et al. Lower serologic response to COVID-19 mRNA vaccine in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases treated with anti-TNFα. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(2):454–467.

40. Cree BAC, Maddux R, Bar-Or A, et al. Serologic response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in DAYBREAK participants with relapsing multiple sclerosis receiving ozanimod [oral presentation OPR-162].

41. Jarvi NL, Balu-Iyer SV. Immunogenicity challenges associated with subcutaneous delivery of therapeutic proteins. Biodrugs. 2021;35(2):125–146.

42. Alqahtani MS, Kazi M, Alsenaidy MA, Ahmad MZ. Advances in oral drug delivery. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:618411.

43. Jonaitis L, Marković S, Farkas K, et al. Intravenous versus subcutaneous delivery of biotherapeutics in IBD: an expert’s and patient’s perspective. BMC Proc. 2021;15(Suppl 17).

44. Hanauer S, Panaccione R, Danese S, et al. Tofacitinib induction therapy reduces symptoms within 3 days for patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(1):139–147.

45. Loftus EV. A practical approach to JAK inhibitors for inflammatory bowel disease in 2020. Pract Gastroenterol. 2020;XLIV(5):36–40.

46. Shim HH, Chan PW, Chuah SW, Schwender BJ, Kong SC, Ling KL. A review of vedolizumab and ustekinumab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. JGH Open. 2018;2(5):223–234.

47. Murray A, Nguyen TM, Parker CE, Feagan BG, MacDonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8(8):5676.

48. Burr NE, Gracie DJ, Black CJ, Ford AC. Efficacy of biological therapies and small molecules in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut. 2021;gutjnl-2021–326390.

49. Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(20):1946–1960.

50. Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Ghosh S, et al. Four-year maintenance treatment with Adalimumab in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: data from ULTRA 1, 2, and 3. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(11):1771–1780.

51. Pfizer Labs. Xeljanz [Package Insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Labs; 2022.

52. Abbott Laboratories. Humira [Package Insert]. North Chicago, IL: Abbott Laboratories (AbbVie); 2021.

53. Janssen Biotech, Inc. Remicade [Package Insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc.; 2021.

54. Degagné E, Saba JD. S1pping fire: sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling as an emerging target in inflammatory bowel disease and colitis-associated cancer. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2014;7:205–214.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.