Back to Journals » Journal of Blood Medicine » Volume 15

Type 1 Gaucher’s Disease. A Rare Genetic Lipid Metabolic Disorder Whose Diagnosis Was Concealed by Recurrent Malaria Infections in a 12-Year-Old Girl

Authors Mitala Y , Birungi A, Mushabe B, Manzi J, Ssenkumba B, Atwine R, Ankunda S

Received 28 October 2023

Accepted for publication 18 January 2024

Published 20 January 2024 Volume 2024:15 Pages 1—7

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JBM.S444296

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Martin H Bluth

Yekosani Mitala,1 Abraham Birungi,1 Branchard Mushabe,2 John Manzi,3 Brian Ssenkumba,1 Raymond Atwine,1 Siyadora Ankunda2,4

1Department of Pathology, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Mbarara City, Uganda; 2Department of Pediatrics, Kabale University, Kabale, Uganda; 3Department of Surgery, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Mbarara City, Uganda; 4Department of Pediatrics, Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital, Mbarara City, Uganda

Correspondence: Yekosani Mitala, Email [email protected]

Introduction: Gaucher disease is a rare autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disease with unknown prevalence in Africa and no record of the disease exists in Uganda.

Case Presentation: We report a case of a 12-year-old female, the last born of 6 from a family with no known familial disease who presented with non-neuronopathic Gaucher disease and superimposed malaria. The disease was initially misdiagnosed as hyperreactive malarial splenomegaly but was subsequently confirmed by examination of the bone marrow smear and core. The disease was managed supportively and splenectomy was done due to worsening hematological parameters. She currently takes morphine for bone pains in addition to physiotherapy.

Conclusion: Always HMS is a common complication in malaria endemic areas, other causes of hepatosplenomegaly need to be excluded before the diagnosis is made. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with rare conditions like GD is still a challenge in developing countries. Although splenectomy is indicated in GD, it should only be done when it is absolutely necessary.

Keywords: type 1 Gaucher’s disease, case report, Uganda

Introduction

Gaucher disease (GD) is an autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disease (LSD), caused by over 300 mutations in the GBA1 gene located on the long arm of chromosome 1, region 2 band 1.1,2 This causes a deficiency of a key lysosomal enzyme called β-glucosidase (also known as glucocerebrosidase) in the leukocytes. This enzyme is critical in the metabolic conversion of glucosylceramides (sugar-containing fat) to glucose and ceramide. Because of its deficiency, glucosylceramides accumulate in the lysosomes (digestive machinery of macrophages), transforming the macrophages into Gaucher cells that characterize Gaucher disease.3 This material/substrate (glucosylcerebroside) is continuously produced by the body but the lysosomes cannot break it down, it gets “stored” in the macrophages, hence its name, LSD. Therefore, these transformed macrophages accumulate in the body’s organs like bone marrow, spleen, liver, and nerves, impairing these organs’ functions.4 GD has no sex predilection and is the second most common lipid storage disease after Fabry disease.5

It is a rare disease with a prevalence of 1 in 100,000 and an incidence of 1 to 60,000 births in the general population.3 The incidence drastically rises to about 1 in 450 births among Ashkenazi Jews.6 In Africa, data is limited, however, a number of cases have been reported by several authors, from South Africa, Morocco, Mali, and Kenya.2,6–8 In Uganda, data about the condition is lacking. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of Gaucher disease to be reported in the country.

The disease can present in either of the 3 forms. The non-neuronopathic form (GD type 1) and the neuronopathic form (GD type 2 and 3).3,9 Type 1 disease is characterized by the absence of neurological involvement and may present with pancytopenia, organomegaly (hepatosplenomegaly), skeletal lesions, and lung and renal involvement. It is the most common form of the disease among the Jews. Type 2 is characterized by central nervous system involvement and is rapidly fatal. It is more common among infants and newborns and is also known as the acute neuropathic form. Type 3 disease also causes central nervous system involvement; however, it takes a more chronic form and also causes hematological and skeletal involvement. Sufferers can live up to 40 years and the disease is known as the chronic neuropathic form.1,5 Types 2 and 3 are more common among the non-European population.1

Case Presentation

A 12-year-old Ugandan female, referred from a peripheral health center with 2 years history of on-and-off spontaneous progressively worsening epistaxis, associated with an 8/12 history of progressive abdominal distension, and mild pain. The bleeding is preceded by a sharp frontal throbbing headache. Two weeks prior to admission, epistaxis worsened with up to 4 episodes per day with an increase in abdominal distension and pain. In the same period, she developed on-and-off low-grade fevers, associated with severe headaches, palpitations, dizziness, and general malaise. She had had 3 admissions last year for which she was managed for malaria, with no blood transfusion. She is the last born of 6 and had no family history of a similar condition.

Examination revealed moderate anemia, mild jaundiced, and nontender mild submandibular lymphadenopathy. Was pyrexic with an axillary temperature of 38.4°C, tachycardic at 120 beats per minute. Other vitals were unremarkable. She had a non-tender moderately distended abdomen, with a massive hepatosplenomegaly (spleen 8cm below the coastal margin and liver 12 cm below the coastal margin) (see Figure 1). Other organ systems were unremarkable.

|

Figure 1 (A) Shows gross hepatomegaly and splenomegaly. (B) Shows the spleen after splenectomy was done. |

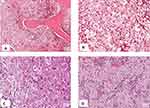

Investigations revealed pancytopenia (Hemoglobin of 5.9g/dl, White cell count of 2100/µL, platelets of 76,000/µL) (See Table 1 for details) on a complete blood count. Peripheral blood smear revealed ring forms of plasmodium falciparum and marked thrombocytopenia. Gross hepatosplenomegaly and scanty mesenteric lymphadenopathy were noted on abdominal ultrasonography. A clinical diagnosis of malaria with hyperreactive malarial splenomegaly (HMS) was made with a differential diagnosis of hematological malignancy. Subsequently, a bone marrow biopsy and aspirate were done. Smears were stained with Giemsa (see Figure 2A and B) while trephine biopsy was stained with H&E and these revealed Gaucher cells) which are weakly periodic acid Schiff (PAS) positive (see Figures 3A–D). Therefore, a diagnosis of Gaucher’s disease was made although enzyme assay for glucocerebrosidase could not be done due to financial constraints.

|

Table 1 Shows Some of the Complete Blood Count Parameters and Other Blood Tests Done on Admission and How They Varied During the Follow-Up Period |

She was managed for malaria with 3 doses of intravenous artesunate, dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine, paracetamol, and folic acid. Because of the lack of definitive treatment for Gaucher’s disease, the family was counseled and discharged on tranexamic acid per required need, fansidar two tablets monthly, and to be reviewed once every month. After 6 months of follow-up, splenectomy was done due to worsening hematological parameters. The procedure was successful, the spleen weighed 695g and was firm solid with no infarcts or discrete nodules seen (see Figure 1A and B). Following splenectomy, the subsequent CBCs initially revealed an upsurge in the leukocytes (14,400/µL), platelets (666,000/µL), and near-normal hemoglobin (10.0g/dl) (done on day 2 weeks post-operatively). Five weeks postoperatively, she was still running a leukocytosis (18,700/µL), a normal hemoglobin (11.4g/dl), but had developed a thrombocytopenia (28,000/µL) (see Table 1). She also had developed severe bone pains in the pelvis and thighs with the inability to walk and stand. She also had episodic fevers. Lower limb x-ray revealed early skeletal deformities (Erlenmeyer flask deformity) (see Figure 4) involving the metaphysis of the femur. There was no evidence of osteonecrosis on x-ray. Her pain was managed by morphine in addition to physiotherapy. She still attends monthly reviews at pediatric oncology clinic and physiotherapy although the prognosis is still not known. Currently, she is back to school and doing fairly well. To further improve her management, we are now in contact with the International Gaucher Alliance who we hope will be key in the subsequent management of her condition. These events are summarized in the attached timeline figure (see Figure S1).

|

Figure 4 X-ray of the femur taken 5 weeks after splenectomy showing early musculoskeletal changes in the bones (Erlenmeyer flask deformity in the right femur). |

Discussion

GD type 1 is the most common form of the disease among the Jewish population with variable age of onset but is common before 20 years of age.10,11 Patients have some residual activity of the enzyme glucocerebrosidase. It is characterized by the accumulation Gaucher cells in the bone marrow, spleen, liver, and kidneys. The central nervous system is however spared. Patients, therefore, present with bleeding diathesis, anemia, increased risk of infections, and abdominal distension due to organomegaly. In this case, there was worsening epistaxis, recurrent malaria infections, and abdominal distension. The previous recurrent attacks of malaria concealed the diagnosis of GD. The initial CBC revealed pancytopenia (see Table 1, first row). Because of the anemia, she had tachypnea, tachycardia, palpitations, and dizziness. These could also have been caused by the high fever of 38.4°C that she presented with because of malaria. She also had epistaxis at presentation which is attributed to thrombocytopenia. Thrombocytopenia can occur in severe malaria and this can easily confound the diagnosis.12 However, in her case, she had been having these episodes of spontaneous epistaxis for the last two years and had reportedly worsened with up to 4 episodes of epistaxis per day. Therefore, malaria infection could not solely explain the worsening epistaxis over the 2 years period.

As reported in all reported cases of type 1 GD, she also had characteristic hepatomegaly and splenomegaly of 12 cm and 8 cm (See Figure 1). Because we are in a malaria-endemic region, splenomegaly with a positive malaria test is always thought to be hyperreactive malarial splenomegaly (HMS). A recent systemic review revealed that up to 76% of splenomegaly in African countries is caused by HMS13 as was also suspected in this case clinically. Because hepatosplenomegaly is not exclusive to HMS, other causes of hepatosplenomegaly need to be excluded to avoid misdiagnosis as it could easily have happened in this case.

Gaucher’s disease can be clinically suspected by the presence of clinical signs and symptoms and the identification of Gaucher cells on histological examination of either splenic, liver, or bone marrow biopsy. These investigations are usually done to investigate other suspected conditions like hematological malignancies as was suspected in this case. In our case, a bone marrow aspirate was done for suspected leukemia. Giemsa stained smears revealed large cells with small eccentric nuclei with basophilic cytoplasmic inclusions which were suspected to be Gaucher cells. Examination of the H&E stained trephine biopsy showed abundant accumulation of macrophages crowding out all hematopoietic cells. The macrophages had eccentric condensed chromatin and abundant cytoplasm with wrinkled paper-like accumulations which were weakly PAS positive. Based on the presence of these cells and the clinical picture, a diagnosis of GD type 1 was reached at. However, although Gaucher cells are pathognomonic for the disease, pseudo-gaucher cells have been reported in several other conditions. Pseudo-gaucher cells are seen in chronic myeloid leukemia, acute myeloblastic leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, myeloma among others.14

Following detection of Gaucher cells, the diagnosis is confirmed by laboratory demonstration of deficiency of glucocerebrosidase enzyme activity in the white blood cells (Beta-glucosidase leukocyte blood test). Patients with type 1 GD usually have some residual activity of the enzyme. Also, the test may not be helpful in carriers for which genetic testing is required to detect variants in the GBA1 gene.1,5 In the case presented, enzyme testing was not done and it is not available in the country. Attempts were made to have it done but the only available option was shipping the sample to India at a cost that the family could not afford.

Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) is the mainstay treatment strategy, especially for type 1 GD. Recombinant glucocerebrosidase enzymes (imiglucerase, velaglucerase alfa, and taliglucerase alfa) are currently in use; however, these are not available in most underdeveloped countries. In our setting, treatment is largely supportive as indicated in the case above and in several cases reported in Kenya.6 After 6 months of supportive care, cytopenia and organomegaly were worsening and therefore a total splenectomy was done despite the adverse consequences. Splenectomy is indicated as one of the treatment options in patients not receiving ERT but the prognosis after the procedure is still debatable. There may be an improvement in hematological abnormalities,15 however, the disease tends to worsen in other organs with an increased risk of pulmonary hypertension and malignancy16 as seen in the case above. After splenectomy, the hematological parameters showed an improvement with hemoglobin in the normal range. The white blood cells improved beyond the normal upper limit and this coincided with a fever although there were no other features of possible infection. Contrary to hemoglobin and white blood cells, platelets remained consistently low, lower than the pre-splenectomy values. Additionally, she started experiencing bone pains with evidence of Erlenmeyer flask deformity but without osteonecrosis. The pain could be a result of sudden increase in the Gaucher cells in the bones following splenectomy. Ultimately, we predict that she will suffer pathological fractures. Other recommended treatment options include substrate reduction using either eliglustat or miglustat. These block the production of glucocerebrosides thus preventing their accumulation in the macrophages.5

Limitations

Confirmation of GD requires enzyme assay to establish deficiency of glucocerebrosidase. In our setting, the test could not be done. The available option was provided by a private laboratory that suggested to ship the blood sample to India, at a cost that could not be afforded by the family.

Conclusion

GD is a rare disease among the Africans. Its symptoms can easily be mistaken for other conditions like HMS seen is malaria-endemic areas. Diagnosis and access to standard care for rare conditions like GD is still a challenge in developing countries like Uganda. Although ERT is the standard of care for GD, splenectomy is still an option especially in low resource settings where ERT is unavailable. Although splenectomy may result in an improvement of the hematological parameters, it should only be done if it is indispensable because of the deterioration that may follow.

Data Sharing Statement

The data and materials of this case report are available from the corresponding author upon request after approval from the Pathology Department and Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital.

Consent and Ethical Approval

Parental consent was obtained to authorize us to publish the case details and other images obtained from her daughter as part of the case. The mother also gave consent to use the remaining specimens for any further research purposes in the future. The head of the pathology department also provided us with clearance to use the laboratory and the specimen. Institutional approval was not required.

Patient Perspective

This being a rare genetic condition, the family was really worried and concerned about their daughter’s condition. What was even more disturbing was the fact that it had no definitive cure and the recommended drugs were not available in the country. The family was counseled and educated about the pattern of inheritance and the type of care that can be provided to them. Fortunately, they are very adherent to treatment and have followed the follow-up schedule to the dot and so far they are satisfied with the care given despite the dismal outcome that the condition bears.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the patient and her family for allowing us to take pictures of their valuable body parts and to use their specimen publication for future research purposes. We also acknowledge the pathology department of Mbarara University and the Oncology Clinic at Mbarara regional referral hospital for the caring for sick.

Funding

This project was not funded and was not intended for profit-making purposes.

Disclosure

The author(s) report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Pastores GM, Hughes DA. Gaucher disease. In: Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, editors. Genereviews(®). Seattle: University of Washington, SeattleCopyright © 1993–2023, University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved; 1993.

2. Sevitz H, Laher F, Varughese S, Nel M, McMaster A, Jacobson B. Baseline characteristics of 32 patients with Gaucher disease who were treated with imiglucerase: South African data from the International Collaborative Gaucher Group (ICGG) gaucher registry. South Afr Med J. 2022;112(1):21–26.

3. Stirnemann J, Belmatoug N, Camou F, et al. A review of Gaucher disease pathophysiology, clinical presentation and treatments. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(2):441. doi:10.3390/ijms18020441

4. Stone WLBH, Master SR. Gaucher disease. 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448080/.

5. Disorders. NNOfR. Gaucher disease: national organization for rare disorders; 2018. Available from: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/gaucher-disease/.

6. Murila F, Rajab J, Ireri J. Gaucher’s disease at a national referral hospital. East Afr Med J. 2008;85(9):455–458. doi:10.4314/eamj.v85i9.9662

7. Traoré M, Sylla M, Traoré J, Sidibé T, Oumar GC. Type 2 Gaucher\’s disease in a Malian family. Afr J Health Sci. 2004;11(1):67–69.

8. Essabar L, Meskini T, Lamalmi N, Ettair S, Erreimi N, Mouane N. Gaucher’s disease: report of 11 cases with review of literature. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20(1):1.

9. Weinreb NJ, Camelo JS Jr, Charrow J, McClain MR, Mistry P, Belmatoug N. Gaucher disease type 1 patients from the ICGG Gaucher registry sustain initial clinical improvements during twenty years of imiglucerase treatment. Mol Gene Metabol. 2021;132(2):100–111. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2020.12.295

10. Dardis A, Michelakakis H, Rozenfeld P, et al. Patient centered guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of Gaucher disease type 1. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022;17(1):1–17.

11. Chaabouni M, Aoulou H, Tebib N, et al. Gaucher’s disease in Tunisia (multicenter study)]. Rev Med Int. 2004;25(2):104–110. doi:10.1016/S0248-8663(03)00267-4

12. Chiabi A, Nguefack S, Kewe I, et al. Massive epistaxis due to profound malaria-induced thrombocytopenia in an adolescent: a case report at the yaounde gynaeco-obstetric and pediatric hospital, Cameroon. Health Sci Dis. 2014;15(3):1.

13. Leoni S, Buonfrate D, Angheben A, Gobbi F, Bisoffi Z. The hyper-reactive malarial splenomegaly: a systematic review of the literature. Malaria J. 2015;14(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12936-015-0694-3

14. Şahin GD, Teke HÜ, Karagülle M, et al. Gaucher cells or pseudo-gaucher cells: that’s the question. Turk J Haematol. 2014;31(4):428–429. doi:10.4274/tjh.2014.0019

15. Adas M, Adas G, Karatepe O, Altiok M, Ozcan D. Gaucher’s disease diagnosed by splenectomy. North Am J Med Sci. 2009;1(3):134–136.

16. Thomas AS, Mehta A, Hughes DA. Gaucher disease: haematological presentations and complications. Br J Haematol. 2014;165(4):427–440. doi:10.1111/bjh.12804

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.