Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 15

Family Medicine Resident Experience Toward Workplace-Based Assessment Form in Improving Clinical Teaching: An Exploratory Qualitative Study

Authors Alruqi I, Al-Nasser S, Agha S

Received 20 July 2023

Accepted for publication 18 December 2023

Published 9 January 2024 Volume 2024:15 Pages 37—46

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S431497

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Ibrahim Alruqi,1– 3 Sami Al-Nasser,1,3 Sajida Agha1,3

1Department of Medical Education, College of Medicine, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 2Family Medicine Department, King Abdulaziz Hospital, Ministry of the National Guard - Health Affairs, Al Ahsa, Saudi Arabia; 3King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Ibrahim Alruqi, Department of Medical Education, College of Medicine, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, P.O. Box 3660, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Tel +966559955575, Email [email protected]

Background: Workplace-Based Assessment (WPBA) has been widely utilized for assessing performance in training sites for both formative and summative purposes. Currently, with the recently updated duration of the family medicine (FM) training program in Saudi Arabia from four years to three years, the possible impact of such a change on assessment would need to be investigated. This objective was to explore the experiences of FM residents regarding the usage of WPBA as an assessment tool for improving clinical teaching at King Abdulaziz Hospital (KAH), Al Ahsa, Saudi Arabia.

Methods: The study involves an exploratory qualitative phenomenological approach targeting family medicine resident in KAH was used. Purposive sampling techniques were used. In this descriptive study, data was collected through the utilization of 1:1 semi-structured interviews guided by directive prompts. All recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. An inductive analytical approach was applied for thematic analysis of transcripts.

Results: Fifteen participants were individually interviewed until data saturation was reached. The themes that emerged were organized into the categories of underlying principles of WPBA, the impact of the learning environment, associated opportunities and challenges, and making WPBA more effective. Participants expressed that the orientation provided by the program was insufficient, although the core principles were clear to them. They valued the senior peers’ support and encouragement for the creation of a positive learning environment. However, time limit, workload, and a lack of optimum ideal implementation reduced the educational value and effectiveness of WPBA among senior residents.

Conclusion: The study examined residents’ experiences with WPBA and concluded that low levels of satisfaction were attributed to implementation-related problems. Improvements should be made primarily in two areas: better use of available resources and more systematic prior planning. Revision and assignment of the selection process were suggested, in addition to the implementation of the new curriculum. The research will assist stakeholders in selecting and carrying out evaluation techniques that will enhance residents’ abilities.

Keywords: medical education, assessment tool, family medicine, experience toward workplace-based assessment form, workplace-based assessment

Introduction

Family medicine (FM) is known as one of the most important specialties worldwide due to the wide range of health services for all individuals regardless of age, gender, or bodily systems. It stands on a few important principles, namely, comprehensiveness, continuity, coordination, and accessibility.1

In Saudi Arabia (KSA), FM was initiated in Riyadh in the early 1980s at the military hospital.2,3 Initially, the Saudi Board of Family Medicine (SBFM) had a four-year-structured training program, which was then shortened to three years in 2019, covering wide aspects of knowledge, skills, and attitudes. The trainer and resident use different strategies to teach and learn various pieces of knowledge and skills throughout the program.4 Owing to the shorter duration of the training, the importance of using formative assessment is in high demand.

At the moment, the importance of clinical teaching and improving the use of assessment tools is gaining more focus compared to the previous years. In regard to teaching, FM residents in the clinic mainly present the challenges of providing appropriate patient care, maintaining efficiency, and incorporating meaningful education for residents under medical training,4 while the main goal of clinical training is to develop physicians with the capability of providing professional, effective, high-quality, and safe clinical care.5 For assessing the performance of residents in the clinic or any site of training, such as inpatient rotation, the formative tools of assessment are recommended. The most commonly employed tools are mini-clinical evaluation exercises (Mini-CEX) and case-based discussion (CBD). In the Mini-CEX, the resident during training is evaluated in multiple aspects, which include history taking, physical examination skills, communication skills, clinical judgment, professionalism, organization/efficiency, and overall clinical care.6

CBDs are known as the type of discussion that can introduce a resident under training to real-world scenarios where they can discuss their opinions and experience and interact with each other, trying to solve the problem in the case by searching for a solution together.7,8 In the literature, Mini-CEX and CBD in a clinic or site teaching are useful for learning and improvement in addition to the known usage as formative assessments globally and locally. They have been used in different learning levels such as for undergraduate studies, internships, or postgraduate residency programs. It is shown that structured written feedback could improve the performance of medical students.4,6,9

Moreover, it has been shown that using these forms can be affected by multiple cofactors in either usage or implementation such as a dual system of learning and assessment between a trainee and trainer, in addition to needs of time or variation in completions.9–11 Reviewing articles show the need of providing support to the trainee to regulate learning in the clinical environment individually in respect of using tools and the support gained by supervisors in the training.9 Another study done for ER interns shows the costly significance to the emergency department due to using Mini-CEX encounters for interns’ performance assessment.10 In addition, the use of CBD for learning increases the knowledge and evidence usage of internal medicine residents.12 However, locally in Saudi Arabia, Mini-CEX and CBD have been used by multiple residency programs as tools of assessment and learning, which shows that they are useful tools for assessing professionalism in medicine.13 They have been well structured in curriculums such as the family medicine program and anesthesia training program.4,14

The introduction of a multidisciplinary approach early in the medical curriculum improves knowledge and skill acquisition. This is reflected in student performance, especially if evaluated using the Mini-CEX format, thus providing rapid feedback to students concerning their performance.15 In response to urgent requirements to expand FM services to achieve the transformative goals of the new Saudi Vision 2030, several curriculum design changes were recommended. A revealing recommendation was to reduce the residency training curriculum to three years, which, in turn, mandated a full review of the curriculum components and processes.4

From this point, the importance of attitude and perception of assessment and learning tools such as Mini-CEX and CBD is raised to ensure reaching the purpose of clinical training, which is to develop physicians with the capability of delivering professional, personal, effective, high-quality, and safe clinical care with intelligent kindness to provide care to the community in Saudi Arabia. For that, the question is raised regarding the attitude and perception of FM residents toward Mini-CEX and CBD forms for clinical teaching. This study aims to explore the experience of FM residents regarding the usage of mini-CEX and CBD as an assessment tool for improving clinical teaching and to determine the factors that can affect the use of WPBA among family medicine residents during training.

Materials and Methods

The current study is an exploratory qualitative phenomenology research targeting family medicine residents at the National Guard training center in KAH, Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs for exploring their experience of Mini-CEX and CBD toward clinical teaching improvement. This study protocol was approved by the Institute Research Board (IRB) at King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (Reference Number SP22R-235-10).

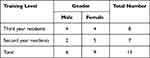

In this study, all 30 current residents were invited to participate. Residents were recruited using a purposeful sampling strategy and a total of 15 residents (7 from second year and 8 from third year) completed think-aloud cognitive interviews, sharing their thoughts on the overall impact of WBPA in the development of students’ clinical capabilities. Among the thirty residents, fifteen gave consent to participate, seven did not respond, six declined, and two were not contacted since the information had reached a saturation point. The collection of data was performed through the utilization of 1:1 interviews using semi-structured questions developed based on the literature review and expert input. The interview questions and probes are presented in the interview guide (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Data Collection tool-Interview Guide. |

The selected participants were emailed an invitation along with a copy of the approved informed consent, which included consent for participation, the right to have the interview recorded, and the right to utilize the transcript responses for research purposes. Additionally, it was emphasized that the contributions would remain anonymous and be used only for research purposes. The interview guide with prompts and the confirmed date and time for the interview was emailed to the participants after obtaining their consent. Only the interviewer and interviewee were present during the interviews, which took place in a professional office at the workplace. In order to reduce the impact of the power dynamics between the interviewer and the participants and to establish norms and open communication throughout the interview, it was made clear during the introduction, ie, the purpose of the interview, the interviewer’s role in the study, assurances of confidentiality, and the freedom to participate or not without consequences or even to withdraw at any time. Each interview lasted for 30–50 minutes. Responses were collected until they reached the point of data saturation. As all participants were multilingual and capable of expressing themselves in the necessary amount of detail, all interviews were done in English using Microsoft Teams. Private and quiet settings were used for the interviews. The researcher gave the assurance that the interview would remain private and that only the research team would have access to the recordings after they were saved. After obtaining permission from the participants, the interviews were recorded and immediately transcribed verbatim by two independent transcribers to avoid any inaccuracy.

The analysis continued both during and after the data collection period. It took several readings and rereading of the interview transcripts to become completely comfortable with the data. The objectives of the study were reviewed frequently to regain focus when new themes and concepts developed. For analyzing the qualitative data, we used thematic analysis to highlight commonalities and patterns in the residents’ responses about their personal experiences through coding and categorizing themes. The interviews were transcribed using Microsoft Office. As an initial step, open coding to analyze individual interview data and researcher field notes was used to identify important words and label them accordingly. These open codes were created for each interview question and given a description in order to facilitate later coding and ensure that all data were relevant to the questions. Accordingly, data were examined using a line-by-line strategy to make certain that all data were appropriately labelled. Later, categories and themes were generated from these codes.

All coding was done by the relevant author, and it was confirmed by the other two authors. The updated analysis was delivered electronically to each team member for a second opinion. The study team then discussed and reviewed the findings during a weekly online discussion. On the final findings, the entire research team concurred.

Results

Fifteen participants were individually interviewed to reach data saturation (Table 1). The emerging themes were organized into the underlying principles of WPBA, the impact of the learning environment, associated opportunities and challenges, and making WPBA more effective (Figure 2). The emerging themes were supported by quotes from the residents’ interviews.

|

Table 1 Study Participants (N = 15) |

|

Figure 2 Themes Generated from Interview. |

The themes encourage trainers and residents should be more actively engaged in learning activities in their respective programs which helps them in remaining involved and enthusiastic about their learning pursuits. All the themes reflected the participants’ understanding of the concepts and the need to develop effective education and training programs to deliver quality healthcare and improve patient outcomes. The fundamentals of communication, opportunity to get timely feedback, clear guidelines, and curriculum update were emphasized by the participants. Arguably, results will enrich the learning environment by establishing the tools of assessment for feedback and better outcomes (See Table 2).

|

Table 2 “Inductive Analysis of Participants on Workplace-Based Assessment” |

Theme One: Underlying Principles of WPBA

The study’s findings showed that every participant was well-informed regarding the presence of situated learning and the opportunities to receive structured feedback from an expert or a trainer.

A third-year male resident notes,

It means the assessment tool is used to assess the resident’s experience, attitude, and skill upon each rotation and how much the resident gains or benefits from the rotation.

All participants agreed that the assessment method ensures that all students should get timely feedback and enables residents to discuss and learn from their trainers. Their understanding can be evaluated in the context of their arguments during the interviews.

---it is a performance assessment in rotation so trainee get timely feedback and get chance to discuss with trainer

Also,

—because family medicine residents deal with many cases so there are benefit like discuss with senior consultants.

More specifically, the majority of participants connected assessment tool to the development of abilities.

it means the assessment tool used to assess the resident experience, attitude, and skill upon each rotation and how much the resident gain or benefit from the rotation.

They also identified that assessing skills in the training program is possible through the assessment tool being used in the training program and providing space for open discussion. Like one said:

I believe to ensure that resident is obtaining skills in related cases and discovering strength and weaknesses, the use of appropriate tool is very important.

Likewise, another resident said,

--value of WPBA come from the formulated discussion and proper documentation. Thus increase chance of discussion with trainer to get maximum benefit.

Theme Two: Impact of Learning Environment

Participants talked about how crucial a student’s environment is for learning. All participants agreed that an orientation program should include information that promote the growth of the necessary skills, and cognitive capacities. They opined that orientation from the program faculty was not adequate. However, senior peers were supportive and helped to create a good learning environment. For instance:

Yes, minimal orientation was given at the beginning of the residency regarding the format as requirement and needed numbers only.

Another participant said:

For example, “the orientation mainly came from the previous batches and senior colleagues’--‘they teach me how to us the form and how to send.

Aside from orientation content, the majority of participants emphasized that it is imperative that orientation programs should also explain the concept, purpose, and use of WPBA.

----they teach me how to use the form, purpose, and how to send.

Theme Three: Associated Opportunities and Challenges

Participants travelled through thoughts to look at ways in which the WPBA contribute to better learning outcomes. While explaining, many participants mentioned that situated learning, and communicating with the trainer, and receiving feedback were perceived as opportunities for WPBA implementation in clinical teaching. Whereas, barriers include time limits in preparation and discussion, considering the workload that can distract from the main rotation, and a lack of ideal implementation can minimize the value of WPBA.

A resident explained,

It can be used as a teaching tool in case of missing some points because it gives a real-time experience through repetition.

Additionally,

‘it can give clear ideas about the disease, the case and the treatment plan.

Residents reflected on the impact of WPBA in time management, communication with seniors, and lack of proper implementation. As second-year resident reported,

WPBA is taking time while at some time the trainer has no time to fill in the form.

In addition,

----load of such tools affects time management and is difficult to communicate with the senior.

----in some rotation cannot be applied properly because there are may not be a full knowledge of specialty or full opportunity to take history/examination and management plan.

Theme Four: Making WPBA More Effective

The participants openly addressed current WPBA practice and emphasized the modifications that are required to improve their knowledge and competence in dealing with residents’ skills building. The majority of participants placed a strong emphasis on updating the curriculum and addressing selection needs in addition to ensuring adequate electronic usage and e-source for WPBA.

In regard to the updated curriculum recommendation, a third-year resident shared,

preferred to be specified for each rotation and for each residency level by SCFHS in the curriculum” in addition to a second-year female resident who notes, “tailoring it (WBPA) according to the content of each rotation will ensure the proper implementation.

To make WPBA more effective, addressing selection needs was recommended, and it has been noted by senior and junior residents who participate in this study. Residents stated:

In each rotation, suggest or select reference trainers for family medicine specialists who are responsible for making an evaluation and overall evaluations.

The majority of participants—nearly half—believed that use of e-tools can improve the use of WPBA however, lack of orientation among trainers and technical problem has reduced its effectiveness. They explained it as:

We believe that to keep trainer oriented about the usage of e-tools, how to use them and post deadlines for more effective use of WPBA.

---also reduce technical problems of One45 because in most of the cases it doesn’t work such as filling the form as paperwork, finding the name of the trainer, and deadlines.

Discussion

This study aims to explore the experience of family medicine residents regarding the usage of WPBA as an assessment tool for improving clinical teaching in the Family Medicine Residency Training Program. In medical education, assessment serves as the guide at every stage of training. Evaluation is a crucial tool in assisting trainees in identifying areas for improvement and areas in which they are competent. It also helps residents acquire the abilities required to deal with a range of circumstances. Additionally, patient safety needs to be given first priority. Participating in evaluations gives recent medical graduates a unique opportunity to advance their careers based on feedback from Workplace-Based Evaluation assessors.16,17

The participants in our study showed that they understood the importance of WPBA principles and that they had a shared understanding of them. This comprehension relates to the basic concepts and definitions associated with WPBA.18,19

Updated curriculum and addressed selection needs were recommended by the participants in the study to reach the individual needs and the different rotation needs; this finding was consistent with the study showing that people who participate in both work and doing WPBA are gradually changing the workplace. Individual experiences and the perception of WPBA authenticity are framed by the environment and culture. In addition, different people tend to learn different things from the same experience.20

Our result is consistent with previous studies that show the use of WPBA can be affected by multiple cofactors in either usage or implementation, assessment between trainee and trainer, in addition to needs of time or variation in completions.9,11 With the presence of these barriers, the educational value of WPBA became low, and this finding is consistent with other studies that show the attitudes of the assessors sometimes reduce WPBA educational value.21

The effectiveness of workplace-based assessment is increased by several criteria, including the provision of feedback that is in line with the needs of the learner and concentrated on key elements of the performance. Faculty must also be properly trained for successful implementation because they play a crucial part.20,22 Orientation programs should be introduced to residents and trainers with the support of curriculum designers.

The results of the qualitative analysis stressed that the healthcare system has a responsibility to access physicians who have undergone extensive training and proven to be competent in delivering safe and efficient patient care. Physician competence is always evolving during the educational process. Accurately evaluating a resident’s level of care and aligning it with a supervision level that supports both professional growth and safe care are essential. Authentic patient-care settings should yield trustworthy data that informs these judgments.23

The current technique of a competency-based workplace assessment system provides data to guide judgments regarding a learner’s “Readiness to care for patients in an inpatient setting without the presence of a supervisor”. However, our residents perceived faculty buy-in and effort to be obstacles, particularly in programs lacking administrative support for assessment.23

Nonetheless, this assessment system provides significant benefit to residency programs seeking to draw critical conclusions about their residents’ readiness for inpatient care in the absence of a supervisor. It is necessary to provide a model for other specialties in order to identify judgments, items, and instruments that address the progression of important abilities required to advance their learners along the continuum towards unsupervised practice.24

Nonetheless, given that WPBA is a worldwide concern, the analysis’s findings are reliable. There are various limitations associated with this research. Due to the inherent generalizability restriction in qualitative investigations, there was limited generalizability. To address this issue, additional data is required in order to extrapolate the findings to different educational settings. Additionally, because this study was restricted to a single institute and a single specialty resident training program, particularly family medicine, this study was unaware of any additional programs or institutes. Further studies should be conducted on residents from various training programs in other training institutions may assess the skill sets of residents exposed to WPBA and investigate the practical implications of these assessment techniques on their clinical abilities. Furthermore, as this study focused only on the trainees, it did not examine the viewpoints of other stakeholders, such as the trainers. To address the mentioned limitations, we recommend that orientation programs should be introduced to residents and trainers with the support of curriculum designers. Moreover, stakeholders should be encouraged to improve implementation of WPBA and overcome associated barriers.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Experience with WPBA was explored with low satisfaction levels found among residents due to implementation-related issues. Experience toward WPBA was highlighted in improving clinical teaching but showed gaps between understanding and implementation.

There were multiple cofactors affecting ideal implementation such as time-related factors or a lack of time and workload, and because of the presence of these obstacles and barriers, the educational value of WPBA is minimal in senior residents compared to junior residents. The area of improvement would be mainly addressing appropriate prior preparation and utilization of available resources. Further studies are recommended, and stakeholders are encouraged to improve and fill the gaps. If training programs intend to equip residents with the skills needed for communities that rely on such residents, they should effectively implement the formative and summative assessment methods utilized in their program.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Rakel RE. Essential family medicine: fundamentals and case studies, Third edition. Essen Fam Med. 2006;2:1–740.

2. Al-Khaldi YM, Al-Ghamdi EA, Al-Mogbil TI, Al-Khashan HI. Family medicine practice in Saudi Arabia: the current situation and proposed strategic directions plan 2020. J Fam Commu Med. 2017;24(3):156–163. doi:10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_41_17

3. Albar AA. Twenty years of family medicine education in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Heal J. 1999;5(3):589–596. doi:10.26719/1999.5.3.589

4. Saudi Commission for Health Science. Scientific Committee Saudi Board of Family Medicine Curriculum. Riyadh: Saudi Commission for Health Science; 2019.

5. Caldwell G. An evaluation of a formative assessment process used on post-take ward rounds. Acute Med. 2013;12(4):208–213. doi:10.52964/AMJA.0320

6. Haghani F, Hatef Khorami M, Fakhari M. Effects of structured written feedback by cards on medical students’ performance at Mini Clinical Evaluation Exercise (Mini-CEX) in an outpatient clinic. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2016;4(3):135–140.

7. Lörwald AC, Lahner F-M, Nouns ZM, et al. The educational impact of Mini-Clinical Evaluation Exercise (Mini-CEX) and Direct Observation of Procedural Skills (DOPS) and its association with implementation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):1–15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198009

8. Sadaf A, Kim S Examining the impact of online case-based discussions on students’ perceived cognitive presence, learning and satisfaction. 16th int conf cogn explore learn digit age, CELDA 2019. 2019;421–424.

9. Kipen E, Flynn E, Woodward-Kron R. Self-regulated learning lens on trainee perceptions of the mini-CEX: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e026796. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026796

10. Brazil V, Ratcliffe L, Zhang J, Davin L. Mini-CEX as a workplace-based assessment tool for interns in an emergency department--does cost outweigh value? Med Teach. 2012;34(12):1017–1023. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.719653

11. Latif A, Hopkins L, Robinson D, et al. Influence of trainer role, subspecialty and hospital status on consultant workplace-based assessment completion. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(4):1068–1075. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.01.013

12. Liu Y, Huang M, Zhou Y, Cai H. Evaluation of a staged case-based discussion curriculum in standardized residency training. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2020;48(2):128–133. doi:10.1002/bmb.21321

13. Guraya SY, Guraya SS, Mahabbat NA, Fallatah KY, Al-Ahmadi BA, Alalawi HH. The desired concept maps and goal setting for assessing professionalism in Medicine. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(5):JE01–5. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2016/19917.7832

14. Boker A. Toward competency-based curriculum: application of workplace-based assessment tools in the National Saudi Arabian Anesthesia Training Program. Saudi J Anaesth. 2016;10(4):417–422. doi:10.4103/1658-354X.179097

15. Atta IS, Alzahrani RA. Perception of pathology of otolaryngology-related Subjects: students’ perspective in an innovative multidisciplinary classroom. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;11:359–367. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S256693

16. Prins SH, Brøndt SG, Malling B. Implementation of workplace-based assessment in general practice. Educ Prim Care. 2019;30(3):133–144. doi:10.1080/14739879.2019.1588788

17. Mughal Z, Patel S, Gupta KK, Metcalfe C, Beech T, Jennings C. Evaluating the perceptions of workplace-based assessments in surgical training: a systematic review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2022;1:2

18. Rethans JJ, Norcini JJ, Barón-Maldonado M, et al. The relationship between competence and performance: implications for assessing practice performance. Med Educ. 2002;36(10):901–909. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01316.x

19. Burford B, Illing J, Kergon C, Morrow G, Livingston M. User perceptions of multi-source feedback tools for junior doctors. Med Educ. 2010;44(2):165–176. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03565.x

20. Martin L, Blissett S, Johnston B, et al. How workplace-based assessments guide learning in postgraduate education: a scoping review. Med Educ. 2022;57(5):394–405. doi:10.1111/medu.14960

21. Nesbitt A, Baird F, Canning B, Griffin A, Sturrock A. Student perception of workplace-based assessment. Clin Teach. 2013;10(6):399–404. doi:10.1111/tct.12057

22. Norcini J, Burch V. Workplace-based assessment as an educational tool: AMEE Guide No. 31. Med Teach. 2007;29(9–10):855–871. doi:10.1080/01421590701775453

23. Warm EJ, Held JD, Hellmann M, et al. Entrusting observable practice activities and milestones over the 36 months of an internal medicine residency. Acad Med. 2016;91(10):1398–1405. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001292

24. Donnon T, Al Ansari A, Al Alawi S, Violato C. The reliability, validity, and feasibility of multisource feedback physician assessment: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):511–516. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000147

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.