Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 15

Medical Education Electives Can Promote Teaching and Research Interests Among Medical Students

Authors Arja SB, Arja SB, Ponnusamy K, Kottath Veetil P , Paramban S, Laungani YC

Received 8 December 2023

Accepted for publication 1 March 2024

Published 7 March 2024 Volume 2024:15 Pages 173—180

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S453964

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Balakrishnan Nair

Sateesh B Arja, Sireesha Bala Arja, Kumar Ponnusamy, Praveen Kottath Veetil, Simi Paramban, Yoshita Chandru Laungani

Medical Education Unit Avalon University School of Medicine, Willemstad, Curacao, Netherlands Antilles

Correspondence: Sateesh B Arja, Medical Education Unit Avalon University School of Medicine, Willemstad, Curacao, Netherlands Antilles, Tel +599-96965682, Email [email protected]

Introduction: Although all residents routinely teach medical students, not all residents are involved in teaching or trained in teaching during undergraduate medical school, as accreditation bodies do not mandate the promotion of teaching skills to undergraduate medical students. With relatively inadequate formal training and residents’ intrinsic time constraints, tactically incorporating formal medical education elective experiences in medical school curricula is understandable. This study explores if medical education electives at Avalon University School of Medicine (AUSOM) can enhance medical students’ interest in teaching and research.

Methods: The medical education elective at AUSOM was developed to give interested medical students an elective experience. The course modules include accreditation/regulation, curriculum development, learning theories, assessments, and research methodology. Students can choose any one of the modules. We offered the medical education elective to twenty-five students in the year 2021. All of them gave feedback at the end of the elective. The data was analyzed qualitatively through framework analysis, which includes familiarization, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing, and defining and naming themes.

Results: Different themes emerged, enhancing the interest in academic medicine, understanding research methodologies, supporting learners, and awareness of learning theories.

Conclusion: Doing medical education electives at AUSOM enhanced students’ interest in teaching, and students reported that they could understand research methodologies, especially those related to medical education. Medical students should have opportunities for electives in medical education, and more research is required to evaluate the effectiveness of medical education electives across medical schools.

Keywords: medical education, electives, medical educational research, medical educators, health science students

Introduction

Teaching has long been seen as an intervention that produces learning as an effect, meaning that effective teaching methods provide better, more impactful learning outcomes leading to satisfactory patient care. This model has been adopted in medical education and its related research field.1 The Flexner Report 1910 emphasized the “poor quality of curricula and teaching facilities, lack of standardization, and the schools” disproportionate emphasis on financial gain.2 This report brought immense reform into medical education in terms of standardization but also sparked some enthusiasm to begin research in medical education. From then on, standardization in medical education was a norm. It led to most, if not all, US medical schools providing a 4-year curriculum to their students, with basic sciences training being provided in the first two years followed by clinical rotations being provided in the final two years.

The notable changes that medical schools have managed to implement in the past three decades are alternate curriculum pathways, including shortened preclinical curricula, dedicated hours of research time, and an early head start in terms of clinical exposure. One major change was the introduction of elective courses after completing core clinical rotations. The elective rotations are of students’ choice versus mandatory core rotations. Implementing electives has been a longstanding concept in Western medical schools, with its full potential only being recognized by the late 1990s in the US.3 Electives have been known to provide several benefits to students in terms of orientation and motivation in their medical school journeys in the West, whereas, in developing countries, electives are pursued to understand the dynamics of treating various diseases in diverse healthcare settings but also to gain experiences not limited to the textbook.4 An elective can be defined as a student-centric experience of a short period, mostly ranging from four to eight weeks in duration, that is undertaken during the final years of medical school wherein students are given a significant element of choice 5 to explore their current interests but also forming new ones in the medical field.6 Student-centered learning allows students to venture into topics beyond the content of the core curriculum,7 thus fueling their cognitive interests and broadening overall competence in decision-making in complex situations.8

Electives being offered in US medical schools are broadly classified into the following five categories: 1) Global Health, 2) Project work, 3) Career choice, 4) Directed elective, and 5) Wellness elective.8 Examples of elective courses offered under these categories range from education to research to community postings and other specialty‑specific courses like laboratory electives, palliative care, neurology, emergency medicine, radiology, etc.9 Some authors in the past have judged the functioning of electives based on formative and summative feedback and evaluations, thus deriving distinct conclusions from each elective.10 Still, electives are known to be the least-researched component of a medical curriculum.11 So, despite their known benefits, they still lack considerable “significant educational innovation and practice” compared to other curricular elements.12 The quality of an elective, regardless of it being international, online, or in person, is affected by components such as “resources, poor organization and planning, and limited faculty expertise”, 13 something that, if worked on, can create a gratifying experience for a medical student.

A medical education elective can be classified as a career choice elective in a non-clinical area, one that is provided as an elective in medical schools worldwide, keeping in mind students interested in pursuing a future career in academics and teaching but also those showing some level of curiosity in the educational research.8 The motive for students to opt for this elective is three-fold:

- To gain a broader perspective of teaching and educational research.

- To gain the opportunity to form contacts.14

- To enhance their chance of obtaining a post-graduate post in a competitive market.15

One of the modules of the medical education elective, important to mention, is learning theories. A deep understanding of learning theories is required not just for medical students but also for the educators who teach medical students. This aids in developing higher-order thinking skills, problem-solving, and critical-thinking skills in medical students. It allows educators to “leverage particular aspects of different learning theories to achieve the learning goals” required.16 Even though all medical school graduates are expected to be medical educators as residents and subsequently as faculty, most medical students receive no formal education in teaching.17 Although all clinical faculty members and residents routinely teach as medical educators, not all Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-accredited residency programs offer formal instruction in teaching.

Studies have reported that about one-third of medical students learn from residents.18 Residents spend almost 20% of their time teaching.19 Residency programs vary in their training for teaching skills to residents. Overall, only 55% of residency directors informed that their programs give residents formal instruction and training in teaching skills.20 Residents as teacher’s curricula are increasingly common in graduate medical education. However, three-fourths of survey respondents in a study believed their residents would benefit from even more instruction and training in teaching skills.20 Residency leaders and faculty spend much time and effort teaching their trainee/resident physicians how to teach despite needing precise data to show which educational techniques best support this goal.21 With a relatively inadequate amount of formal training on teaching and intrinsic time constraints faced by residents, strategically incorporating formal medical education elective experiences into undergraduate medical school curricula (undergraduate medical students) seems understandable.

Medical schools must provide opportunities for students to develop scholarly and research skills as stipulated by formal medical school accreditation standards.22 However, there are no formal accreditation standards mandating the fostering of teaching skills to undergraduate medical students.23 Most medical students reported being confident in giving presentations, but fewer were confident in bedside teaching.23 There is literature evidence suggesting the impact of peer tutoring, teaching assistant programs by medical students, near-peer teaching, and even the long-term benefits of peer teacher training through sustained improvements in participants’ self-assurance and perceived ability in teaching skills.24 However, only a few have gone on to explore feedback and evaluation from students on a medical education elective led by a faculty member of their respective medical school. This study is the first of its kind regarding medical education electives and their impact on students’ interest in teaching and educational research across the Caribbean medical schools. It explores if medical education electives at Avalon University School of Medicine (AUSOM) can enhance the interest of medical students (future physicians) in teaching and research.

Methods and Materials

Intervention/Establishment of Medical Education Unit and Offering Electives

The medical education unit (MEU) was established at AUSOM in 2019.

The medical education unit at AUSOM started offering electives in medical education to students in 2020. The medical education elective provided students with broad exposure to several aspects of medical education which are pertinent to their future careers as physicians. The elective provided a platform for students to engage in discussion with faculty members to discuss topics often not included in the medical school curriculum, including teaching methods and learning theories, assessment methods, curriculum development, and educational research methodology. The goal of the elective is to encourage students to understand and appreciate the role of medical education in their development as thoughtful and effective teachers or clinical preceptors in the future and gain knowledge of medical education research. The most chosen modules by our medical education elective students are learning theories and educational research methodology. A total of 25 students completed this elective in 2021.

The available modules are.

- Assessments

- Educational Research Methodology

- Curriculum Development

- Learning

- Accreditation and regulation

Appendix 1: The medical education course content and syllabus description.

Research Procedure

This qualitative phenomenology study explored students’ experiences and perceptions regarding the impact of medical education electives. Phenomenology allows researchers to explore people’s subjective experiences.25 We employed framework analysis to analyze the data of feedback received from students.

Data Collection (Sample and Instruments) and Data Analysis

The students who did medical education electives were 4th-year medical students (undergraduate students) and were the participants/respondents of this study. The sampling technique was purposive convenience sampling, as the survey was distributed to students who took the medical education elective only. The rationale behind this sampling technique was that these students had experienced the medical education elective, and the investigators used the qualitative phenomenology method to explore the students’ subjective experiences and perceptions 25 regarding the impact of this medical education elective on students’ interests in teaching and educational research. We sent an online survey to all students who did medical education elective, with open-ended questions. The survey was created on SurveyMonkey, and the survey link was sent to all students by email. The survey was developed based on the course and clerkship evaluations survey that we have at our institution. The participation of students in this survey was voluntary and anonymous. The survey was open for students for three weeks. Data was stored in the central server of the IT department at AUSOM. None of the investigators or any other faculty could access this information. The investigators got the compiled responses on SurveyMonkey from the IT department. The feedback (responses) was submitted to the investigators and faculty members of the medical education unit after submitting the grades of students on student information system (SIS). The responses of students and the survey will be deleted from the server within five years, and no personal information of students was identified through surveys.

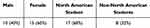

The response rate was 100% and all 25 students provided feedback in 2021. The students who took the medical education elective and completed the online survey represent the general demographics of the Avalon student population. The admissions criteria have not changed for Avalon from 2017 to 2022, which also ensures the consistency of the sample, who are in their fourth year and represent the general student population of Avalon. Table 1 represents the sample demographics. The sample represents 40% male and 60% female students, comparable to Avalon’s male and female students’ ratio (45% and 55%, respectively). Also, the sample represents 68% North Americans (USA and Canadian citizens), comparable to the North American student ratio (70%) of the general population of Avalon and even the case with non-North American students.

|

Table 1 Sample Size and Their Demographics (n=25) |

The survey included open-ended questions such as, what changes would students recommend improving this elective? What are the major strengths of this elective? What are the major weaknesses of this elective? Any further constructive comments? The feedback was analyzed (qualitative data analysis) using framework analysis method. Framework analysis included familiarization, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, and defining and naming themes.26 Data familiarization was the initial stage of thematic analysis.27 This stage involved complete immersion of the authors into the data, by repetitively reading and searching the data for underlying patterns. Code generation was the phase in which codes were implemented as a mode of identification of the relevant data.27 The initial generation of codes and open coding was done by two authors (SA and PK). If there was a disagreement, it was resolved by another author (SBA). Theme searching was the next phase, where the codes were grouped into potential themes.

The review of themes is a phase of refinement, where newly developed themes were altered to be more concise, and more tangible.27 This was achieved through reviewing the consistency of coded data in relation to the established themes. After this, the consistency of the themes was measured against the whole data set, and additional data not included in the initial coding stage was extracted from within the themes.27 The themes were then named and defined appropriately so that it may highlight various aspects of the coded dataset.27 After analyzing the feedback from 25 students, we were not generating new codes and we reached data sufficiency.28 The generated themes and description of the themes were shared with all 25 participants for member checking.29

Ethical Considerations

The ethical approval for this study was exempted by the research and ethics committee of AUSOM. Informed consent was taken from all participants (students), and they had a right to decline to provide feedback, which is voluntary and anonymous. The informed consent included that the course evaluations taken at the end of this elective will be used for evaluation and research purposes, and anonymous responses could be used for publication without identifying personal information.

Results

The response rate was 100% and all 25 students provided feedback in 2021. The themes that were generated based on data analysis are enhancing the interest in academic medicine, understanding research methodologies, supporting learners, and awareness of learning theories. No adverse comments, meaning feedback that opposes the emerging themes, were found within the input.

Theme 1: Enhancing Interest in Academic Medicine

As reported in many of the feedback forms, one of the common benefits of medical education electives was enhancing interest in academic medicine. Four students mentioned that they had never thought of being involved in teaching as a future physician. But after completing this elective, they are considering balancing clinical and academic practice. They want to be involved in teaching medical students in addition to patient care. A few of the quotes to be mentioned are.

One day, I hope to work in academic medicine, and this elective has helped me develop a perspective on the nature of medical education.

I am considering being involved in teaching medical students. I never thought of taking up an academic career. I am considering having balanced clinical practice and teaching medicine.

Theme 2: Understanding Research Methodologies

One of the most popular modules among students in medical education electives at AUSOM is the research methodology module. Students reported that they could understand research methodologies, especially those related to medical education, and implement them in their research projects. A few of the quotes to be mentioned/worth mentioning are.

I learned a lot about research methodology during this Medical Education elective. Thank you for all the reading materials, assignments, and feedback you provided me with over the past few weeks. I appreciate your time and guidance during this elective. This medical education elective was a great experience.

The elective was very informative and made me understand the depth of research. It also provided me with a systematic way to look at research and gave me a look into medical education as well. I plan to get into a hybrid career where I can practice and be involved in academics, so this elective was very helpful.

I will implement the fund of knowledge related to research methodologies gained into my paper. I appreciate your insights during this course.

Theme 3: Awareness of Learning Theories and Supporting Learners

The other most popular module in this medical education elective at AUSOM is learning theories. Students felt that they were able to understand the learning theories behind education. They also understood the different kinds of support systems (supporting learners) required in a medical school. A few of the quotes are.

I have learned so much over this short time regarding aspects of support that students need during medical school, the different learning theories that students utilize to acquire knowledge, and analyzing how simulation can be a huge asset for students in developing interpersonal and communication skills.

I just wanted to say that I truly enjoyed this course. It’s fascinating to learn the theories and specifics behind education. Thank you for offering and allowing me to take this course.

Discussion

The benefits associated with medical education electives for medical students include having a broader perspective of teaching and research and increasing the chances of getting into postgraduation programs.15 The additional themes that were identified in this study are aware of learning theories and supporting learners. As medical educators to medical students, residents (postgraduate trainees) are not involved in teaching prior or are never trained in teaching. Therefore, the authors suggest that medical education electives during medical school will prepare medical students to be good medical educators.

Every physician is someone’s teacher.30 They, without a doubt, teach what they know to students, patients, patients’ families, colleagues, and other healthcare professionals. Society requires physicians to be excellent clinicians and have many other qualities, such as high standards of professional and ethical behaviors, to be good researchers, health advocates, collaborators, teachers and leaders. To inculcate these qualities, substantial curricular changes are required, and it is a very tough task to include new things in an already crowded medical curriculum.

Literature suggests that clinicians and residents actively teach.18,19 However, there needs to be more formal training specifically focused on instructing and teaching medical students.17 Many residency program directors express that residents could benefit from formal instruction and training sessions for residents in teaching skills and competencies.20 Additionally, residency program directors and faculty invest time in training residents on teaching skills.21 However, implementing teaching curricula for residents may be hindered by time constraints, particularly exacerbated by ACGME work-hour policies. The exposure of undergraduate medical students to medical education electives and teaching curricula has the potential to foster interest in academic medicine and teaching, as evidenced by this study (one of the themes identified in this study, (enhancing interest in academic medicine). The medical education elective also helped students understand research methodologies (theme 2) and enhance their interest in educational research, as mentioned by some students in this study.

Understanding learning theories is required for medical students, which fosters higher-order thinking skills, problem-solving, and critical-thinking skills in medical students. It was identified from the emerging themes that studying medical education elective can enhance students’ awareness of underlying learning theories (theme 3) or rationale. Studying and understanding medical education and learning theories can enable students to become more responsible and important stakeholders. Acquiring knowledge of medical education can increase student self-confidence when expressing their thoughts on changes to the curriculum and learning environment. Increased expertise and confidence in education can help students speak up and more actively contribute to the school’s decision-making processes. Current trends in medical education have switched from teacher-centered to learner-centered learning, including academic accountability and student participation in the decisions of change processes of medical schools.31 Student involvement is often restricted to passive feedback or the beliefs of student representatives.32 To address these challenges and encourage robust student engagement, fostering a cooperative mindset among both students and faculty members is essential.33 Medical students were advised to engage in studying medical education should they aspire to enhance the school by actively contributing their insights and voices to curriculum development.30 Medical education might increase students’ confidence in understanding education and learning theories and rationale behind the change processes, encouraging students to involve medical schools’ decision-making process.30

Practice Points (Practical Implications)

- Undergraduate medical students should be allowed to undertake medical electives within their respective institutions, as they will eventually transition to teaching roles once they become residents.

- Medical education electives may include various modules such as teaching methods (skills), learning theories, and research methodologies.

- Participation in medical education electives has the potential to stimulate students’ interest in teaching and educational research.

- Further research and funding are essential to evaluate the effectiveness of medical education electives in different medical schools.

Limitations

One of the limitations of this study is it was conducted at a single institution. The other limitation is feedback was collected and analyzed for one year. Longitudinal analysis is required over the years to evaluate the medical education elective effectiveness at AUSOM. However, these medical education electives can be implemented at any other North American medical school, as the curriculum of Avalon is based on the North American model of the medical curriculum. The other limitation is that three of the investigators involved in this study are faculty of the medical education unit, which could lead to potential personal bias, which was avoided by using reflexivity. The strength of this study was one of the student investigators did a medical education elective at AUSOM.

Conclusions

Upon participating in the medical education elective at AUSOM, students reported an enhanced interest in teaching and an improved understanding of research methodologies, particularly those relevant to medical education. They noted an increased understanding of various learning theories and their application in education and the ability to support learners effectively. This knowledge of medical education and learning theories holds potential benefits for medical schools, empowering learners to engage actively in teaching when they graduate and become residents. Implementing a suitable curriculum within the medical education elective is imperative to realize these benefits. Medical students should be allowed to pursue electives in medical education, allowing them to develop proficiency as effective educators. It is recommended that medical schools introduce medical education electives as a standard offering. Furthermore, additional research and funding are necessary to assess the efficacy of medical education electives across various medical schools.

Ethical Approval

The Research and Ethics Committee of Avalon University School of Medicine exempted this study.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was taken from all participants (students), and they had a right to decline to provide feedback, which is voluntary and anonymous. The informed consent included that the course evaluations taken at the end of this elective will be used for evaluation and research purposes, and anonymous responses could be used for publication without identifying personal information.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the students who provided feedback at the end of the medical education elective.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Biesta GJJ, van Braak M. Beyond the medical model: thinking differently about medical education and medical education research. Teach Learn Med. 2020;32(4):449–456. doi:10.1080/10401334.2020.1798240

2. Atluru A, Wadhwani A, Maurer K, Kochar A, London D, Kane E, and Kayce Spear. Research in Medical Education a Primer for Medical Students. AAMC, OSR medical education committee; 2015. Available at https://www.aamc.org/media/24771/download.

3. Mahajan R, Singh T. Electives in undergraduate health professions training: opportunities and utility. Med J Armed Forces India. 2021;77(Suppl 1):S12–S15. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.12.005

4. Mathur M, Mathur N, Verma A, Kaur M, Patyal A. Electives in Indian medical education: an opportunity to seize. Adesh Univer J Med Sci Res. 2023;4(2):53–55. doi:10.25259/AUJMSR_42_2022

5. Lumb A, Murdoch-Eaton D. Electives in undergraduate medical education: AMEE Guide No. 88. Med Teach. 2014;36(7):557–572. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2014.907887

6. Ramalho AR, Vieira-Marques PM, Magalhães-Alves C, Severo M, Ferreira MA, Falcão-Pires I. Electives in the medical curriculum - an opportunity to achieve students’ satisfaction? BMC Med Edu. 2020;20(1):449. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02269-0

7. Koceic A, Mestrovic A, Vrdoljak L, et al. Analysis of the elective curriculum in undergraduate medical education in Croatia. Med Edu. 2010;44(4):387–395. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03621.x

8. Shumylo MY. The role of elective courses in higher medical education during pre-clinical years. Sci Edu New Dimen. 2019;VII(209):45–48. doi:10.31174/send-pp2019-209vii86-10

9. Salam A, Zainol J. Students’ elective in undergraduate medical education and reflective writing as method of assessment. Intern J Human Health Sci. 2022;6(4):351. doi:10.31344/ijhhs.v6i4.472

10. Elam CL, Sauer MJ, Stratton TD, Skelton J, Crocker D, Musick DW. Service learning in the medical curriculum: developing and evaluating an elective experience. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15(3):194–203. doi:10.1207/S15328015TLM1503_08

11. Jolly B. A missed opportunity. Med Edu. 2009;43(2):104–105. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03264.x

12. Banerjee A, Banatvala N, Handa A. Medical student electives: potential for global health? Lancet. 2011;377(9765):555. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60200-6

13. Jeffrey J, Dumont RA, Kim GY, Kuo T. Effects of international health electives on medical student learning and career choice: results of a systematic literature review. Family Med. 2011;43(1):21–28.

14. Houlden RL, Raja JB, Collier CP, Clark AF, Waugh JM. Medical students’ perceptions of an undergraduate research elective. Med Teach. 2004;26(7):659–661. doi:10.1080/01421590400019542

15. Kassam N, Gupta D, Palmer M, Cheeseman C. Comparison of medical students’ elective choices before and after the abolition of rotating internships. Med Edu. 2003;37(5):470–471. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01487.x

16. Kay D, Kibble J. Learning theories 101: application to everyday teaching and scholarship. Adv Phys Edu. 2016;40(1):17–25. doi:10.1152/advan.00132.2015

17. Harvey MM, Berkley HH, Pg O, Durning SJ. Preparing future medical educators: development and pilot evaluation of a student-led medical education elective. Mil Med. 2020;185(1–2):e131–e137. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz175

18. Snell L. The resident-as-teacher: it’s more than just about student learning. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(3):440–441. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-00148.1

19. Fromme HB, Whicker SA, Paik S, et al. Pediatric resident-as-teacher curricula: a national survey of existing programs and future needs. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):168–175. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-10-00178.1

20. Morrison EH, Friedland JA, Boker J, Rucker L, Hollingshead J, Murata P. Residents-as-teachers training in U.S. residency programs and offices of graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2001;76(10 Suppl):S1–S4. doi:10.1097/00001888-200110001-00002

21. Morrison EH, Hafler JP. Yesterday a learner, today a teacher too: residents as teachers in 2000. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1):238–241. doi:10.1542/peds.105.S2.238

22. Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and structure of a medical school - (LCME Standards): standards for accreditation of medical education programs leading to the M.D. degree. Standard 3 and 7; Available from https://lcme.org/publications/.

23. Matthew HJD, Azzi E, Gw R, Cj R, Khamisa K. A survey of senior medical students’ attitudes and awareness toward teaching and participation in a formal clinical teaching elective: a Canadian perspective. Med Edu Online. 2017;22(1):1270022. doi:10.1080/10872981.2016.1270022

24. Karia CT, Anderson E, Burgess A, Carr S. Peer teacher training develops ”lifelong skills”. Med Teach. 2023;46(3):373–379. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2023.2256463

25. Ramani S, Mann K. Introducing medical educators to qualitative study design: twelve tips from inception to completion. Med Teach. 2016;38(5):456–463. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2015.1035244

26. Lacey A, Luff D Qualitative Research Analysis. The NIHR RDS for the East Midlands / Yorkshire & the Humber; 2009.

27. Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. In: APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. Vol. 2. research designs. Washington (DC):: American Psychological Association; 2012.

28. LaDonna KA, Ar A Jr, Balmer DF. Beyond the guise of saturation: rigor and qualitative interview data. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(5):607–611. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00752.1

29. Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member checking: a tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Quali Health Res. 2016;26(13):1802–1811. doi:10.1177/1049732316654870

30. Oh W, Choi J, Lee J, Jeong R, Oh S. What we learned from a medical education elective program at a medical college. Korean J Med Edu. 2020;32(3):257–259. doi:10.3946/kjme.2020.173

31. Harden RM, Laidlaw JM. Essential Skills for a Medical Teacher.

32. Seale J, Gibson S, Haynes J, Potter A. Power and resistance: reflections on the rhetoric and reality of using participatory methods to promote student voice and engagement in higher education. J Further Higher Edu. 2015;39(4):534–552. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2014.938264

33. Burk-Rafel J, Harris KB, Heath J, Milliron A, Savage DJ, Skochelak SE. Students as catalysts for curricular innovation: a change management framework. Med Teach. 2020;42(5):572–577. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1718070

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.