Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 15

The Experience of Medical Scribing: No Disparities Identified

Authors Levi BH, Ekpa N, Lin A, Smith CW, Volpe RL

Received 12 September 2023

Accepted for publication 20 December 2023

Published 5 March 2024 Volume 2024:15 Pages 153—160

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S439826

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Benjamin H Levi,1,2 Ndifreke Ekpa,3 Andrea Lin,4 Candis Watts Smith,5 Rebecca L Volpe1

1Department of Humanities, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA, USA; 2Department of Pediatrics, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA, USA; 3University of Houston, HCA Houston Healthcare Kingwood, Houston, TX, USA; 4Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA, USA; 5Department of Political Science, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

Correspondence: Benjamin H Levi, 500 University Drive, Department of Humanities, H134, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, PA, 17033, USA, Tel +1 717 531 8778, Email [email protected]

Introduction: The chronic failure to significantly increase the number of underrepresented minorities (URM) in medicine requires that we look for new mechanisms for channelling URM students through pre-medical education and into medical school. One potential mechanism is medical scribing, which involves a person helping a physician engage in real-time documentation in the electronic medical record.

Methods: As a precursor to evaluating this mechanism, this survey pilot study explored individuals’ experiences working as a medical scribe to look for any differences related to URM status. Of 248 scribes, 159 (64% response rate) completed an online survey. The survey was comprised of 11 items: demographics (4 items), role and length of time spent as a scribe (2 items), and experience working as a scribe (5 items).

Results: The vast majority (> 80%) of participants reported that working as a medical scribe gave them useful insight into being a clinician, provided valuable mentoring, and reinforced their commitment to pursue a career in medicine. The experiences reported by scribes who identified as URM did not differ from those reported by their majority counterparts.

Discussion: It remains to be seen whether medical scribing can serve as an effective pipeline for URM individuals to matriculate into medical school. But the present findings suggest that the experience of working as a medical scribe is a positive one for URM.

Keywords: medical scribing, under-represented minorities, URMM, medical school, pipeline

Introduction

Despite the importance of a diverse physician workforce,1–5 there has been stagnation in the matriculation of underrepresented minorities (URM) in medicine over the last 20 years.6–8 In 2009, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education recommended the creation of pipeline programs to increase both the interest and access of URM students to careers in medicine.9 In addition to improving equity, greater minority representation among physicians is valuable because patients who identify with their physicians in terms of ethnicity and self-identified gender have better communication with clinicians, healthcare outcomes (including newborn mortality and inpatient deaths), and greater patient satisfaction.10–14 So, too, racial concordance between physicians and their patients has been associated with increased use of preventive care, decreased emergency department usage, and decreased overall healthcare costs, even after controlling for socioeconomic status.14–16 The COVID pandemic has further illuminated how social determinants of health contribute to health inequality, and raised awareness of the need for a more diverse physician workforce.4,17

Despite growing calls for better pipeline programs to help create a more diverse physician workforce,8,18,19 declining interest in medicine among URM students during their college years has made for a leaky pipeline.20 Moreover, limited diversity amongst administration, faculty, and admissions committees often sends the message that medicine is not a particularly welcome space for URM individuals.20 Accordingly, new mechanisms are needed to successfully channel URM students through pre-medical education and into medical school. One potential mechanism is medical scribing, a paid employment opportunity in which an individual is first trained and then partnered with a healthcare provider to document clinical encounters with patients. Unlike advanced practice providers who elicit histories, conduct physical exams, and make medical decisions, medical scribes merely document what transpires in clinical interactions.

Medical scribing has grown in popularity over the past two decades, fueled by the expansion (and corresponding burden) of electronic medical record-keeping.21,22 Medical scribing has also become a valuable addition to medical school applications, given the opportunities it affords for clinical exposure, career mentorship, advising, and general preparation for medical school.23–26 That said, the few studies examining medical scribing from the perspective of scribes23,25 have not explored whether the experience of scribing might be different for URM scribes. Approximately 10–15% of medical scribes are individuals from historically under-represented groups, notably Blacks and Latinos (A. Yasrebi, personal verbal communication with one of the authors, 2019), many of whom have fewer economic and educational resources compared to majority-background applicants to medical school.27 Since there is potential for URM scribes to have negative experiences in the medical environment due to microaggressions or inadequate mentoring, 28,29 before medical scribing can be considered a promising new pipeline we should first ensure that the scribe experience for URM is not itself beset with problems that undermine its goals.

This study addresses this gap in knowledge by exploring individuals’ perceptions of their experience working as a medical scribe and then analyzing the data for potential differences among individuals who identify as URM.

Methods

Survey Design and Implementation

In collaboration with the Qualitative and Mixed Methods Core at Penn State College of Medicine, a 12-item survey was created and assessed for face validity, pilot tested with a convenience sample of medical students who had previously worked as scribes, and then revised based on participant feedback. The survey was administered online in the Spring of 2021 using a secure REDCap database and included questions about demographics (4 items), role and length of time spent as a scribe (2 items), and the following 5 items about one’s experience working as a scribe:

- Scribing reinforced my commitment to pursue a career in medicine. (1–5 Likert scale)

- Scribing gave me valuable insight into practicing medicine. (1–5 Likert scale)

- As a scribe, I have received valuable mentoring from healthcare providers. (1–5 Likert scale)

- As a scribe, I have been treated fairly by healthcare providers. (1–5 Likert scale)

- Have you had any experiences as a scribe that have discouraged you from pursuing a future career in medicine? If yes, please elaborate below. (Free text)

Participants were recruited from employees of ScribeAmerica working in Eastern Pennsylvania, Northern Maryland, and Delaware- an area that fell under the same regional management as the investigators’ home institution. ScribeAmerica, a private company that provides full- and part-time medical scribes to hospitals and medical practices, was chosen as a partner in this project due to their majority share of the scribe market in the Northeast and their willingness to share the email addresses of scribes who met the inclusion criteria. Potential participants were scribes working in-person in Eastern Pennsylvania, Northern Maryland, or Delaware who had completed the mandatory ScribeAmerica training and had worked with a healthcare provider for at least one week. These potential participants were sent an initial recruitment email with a summary explanation of the research and a link to the survey, and non-responders received up to 3 follow-up emails. It was explained that only those individuals who consented to participate in the study, including having their anonymized responses published, should proceed to the survey. The study was approved by Penn State’s Institutional Review Board (CATS 00015875).

Statistical Analysis

The nonparametric tests Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U were used to analyze the data. Kruskal–Wallis was used with multiple pairwise comparisons to analyze the demographic variables of education, length of time scribing, race/ethnicity, and income. SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to conduct the statistical analysis.

Results

Participants

Of the 248 scribes invited to participate in the study, 159 (64% response rate) completed the survey. The majority were female (76%) and white (52%), had completed a bachelor’s degree (70%), and had worked as a scribe for over a year (58%). Roughly one-third of scribes reported that their family’s annual income was <$50,000 per year, and 20% of scribes in the sample self-identified with a race/ethnicity that qualified as URM. The overwhelming majority (93%) of the respondents reported interest in becoming a healthcare provider, with “physician” being the most frequently identified professional role (72%). (For detailed demographic data, see Table 1).

|

Table 1 Participant Demographics |

Perceived Value

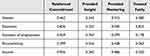

Overall, participants reported that the experience of scribing was positive. Specifically, 95% Agreed or Strongly Agreed that the experience of scribing gave them valuable insight into the practice of medicine, 87% Agreed or Strongly Agreed that it reinforced their commitment to pursue medicine as a career, and 81% Agreed or Strongly Agreed that it afforded them valuable mentoring experiences (see Table 2). When analyzed for associations with self-identified race/ethnicity, minor variations were observed (see Table 3), but none rose to the level of statistical significance. Further, no significant differences in the perceived value of scribing were correlated with participants’ gender, time spent working as a scribe, or family income (see Table 4). That said, one significant difference in the scribing experience was identified regarding education. Scribes who had completed college and/or graduate school were more likely to report having received valuable mentoring compared to scribes who had not finished college (77% vs 23%, p=0.03). No other associations were identified with respect to scribes’ educational level (including any association between education and race/ethnicity).

|

Table 2 Perceived Value of scribing—percent (Count)* |

|

Table 3 Mean Likert Scores for Perceived Value of Scribing, Categorized by Race/Ethnicity (1=Strongly Disagree, 5= Strongly Agree) |

|

Table 4 Association Between Scribe Demographics and Perceived Value of Scribing (Table Shows p-values from Kruskal Wallis Tests) |

When presented with an opportunity to offer critical remarks about experiences that may have discouraged them from pursuing a future career in medicine, many respondents instead used the chance to express how scribing had been a positive, reinforcing experience:

Scribing has reinforced my desire to become a physician based on the physicians I work with. (participant 135, female)

Occasionally there will be difficult patients to deal with, however this is not exclusive to medicine, as there are difficult people in nearly every profession. Even with scribes, doctors must spend a significant time working in the electronic chart and doing “paperwork” outside of seeing patients. While these two things are discouraging, they are not enough to deter me from the field. (participant 42, male)

[Scribing] makes you see that being a physician is not a glamorous profession. It is one that takes up many hours of your time and can be emotionally heartbreaking. I think knowing the ins and outs of what it takes to be a physician, though, has solidified my desire [to be] in the healthcare field. (participant 16, female)

That said, 24 of the 72 participants (33%) who responded to this question did identify negative aspects of working in healthcare, with the majority focused on the difficulty of maintaining an acceptable work-life balance as a physician. Representative responses include:

I feel like the work-life balance I have observed is not suitable for me. (participant 231, female)

The physicians often complain[ed] of the lifestyle… [T]he true realities of the job … [are] not a bad thing by any means. But it definitely made me look at other options. (participant 98, female)

[Something] that discourage[s] me from pursuing a future career in medicine is the difficulty dealing with insurance companies and having things denied when I know they would be a benefit for the patient at the present time, which I have seen firsthand as a scribe. (participant 59, male)

Another negative theme involved personal interactions involving patients and/or providers.

I have seen providers treated poorly by patients, which does concern me and [impacts] my desire to work in healthcare. (participant 117, female)

Many of the providers I have worked with have show[n] no compassion to their patients. Not only do [some doctors] have racist tendencies that affect their treatment plan, but they also have been disrespectful to myself and their staff. They have steered me away from pursuing medical school. (participant 55, female)

To put this last response into context, while 80% of respondents reported that they were treated fairly while working as a scribe, 12% gave neutral responses, and 8% Disagreed or Strongly Disagreed with that sentiment—with no statistically significant differences associated with regard to self-identified race/ethnicity (see Tables 3 and 4).

Discussion

This study found no significant differences in the scribing experience between URM individuals and their majority counterparts. Participants generally perceived working as a medical scribe as a very positive experience that reinforced their commitment to pursue medicine as a profession. This was true irrespective of race/ethnicity, gender, family income, or time on the job. The vast majority of the scribes (93%) reported that they planned to pursue a career in medicine, of whom >70% expressed the desire to become a physician. Though this is a small study, the findings are heartening insofar as scribing appears to offer positive mentoring opportunities while reinforcing scribes’ medical career goals for both URM and majority-group individuals. Moreover, scribes in this study who identified as Black (11%) or Latino (9%) exceeded the percentage of US medical students who identify as Black (6%) or Latino (5%).30 It remains to be seen whether medical scribing can serve as a viable bridge into medicine for URM individuals. But URM scribes in this study reported being treated fairly by healthcare providers and (consistent with prior research)23,25 gaining valuable insight into the lived experience of being a healthcare provider. Having such realistic expectations is important not only for helping individuals gauge whether medicine is a good career fit but also for avoiding the disillusionment that can lead to physician attrition.31,32

The overwhelming majority of URM scribes in the present study did not report being subject to poor mentoring, unfair treatment by healthcare providers, or experiences that would discourage them from pursuing a career in medicine—which is particularly notable given that scribes’ working conditions involve significant imbalances in power.28 One possible explanation for this is the value that clinicians have come to place on well-trained medical scribes as the burden of medical documentation escalates. As the tagline for one scribe company goes: Doctors save lives. Scribes save doctors. Though only one of the 159 participants in our study reported a negative experience with a clinician involving racism (quoted above), its presence calls attention to a concern that should be explored further in larger studies.

That said, if the present findings are generalizable, then working as a medical scribe may provide URM premedical students with much-needed support—in the form of mentoring, encouragement, and, most of all, clinical experience—for getting into medical school. Provided that this is true, the optimal timing for this experience remains unclear. The fact that scribes in the study with higher levels of education found clinicians’ mentorship more valuable may indicate that individuals further along in their education can better appreciate the relevance and applicability of the advice they receive.

Considerably more research is needed to both confirm the generalizability of the current findings and examine the viability of medical scribing as an effective pipeline. However, if it can function as a conduit without major leaks, gaps, or other structural flaws, medical scribing has the potential to help greater numbers of URM applicants become practicing clinicians.

Limitations and Future Directions

The generalizability of this pilot study is limited by its relatively small sample size and recruitment from just one scribe company. That said, it had a very good response rate, especially for online surveys, and its racial/ethnic composition is broadly representative of US medical schools.30 Another limitation is that the survey format did not allow for in-depth exploration (eg, semi-structured interviews) of scribes’ experiences, including the nature and type of any racism that was experienced –which future studies should seek to elucidate. Additionally, the present study only focused on scribes’ on-the-job experiences and did not examine barriers to becoming a medical scribe (such as transportation, need for a higher salary, or perceived self-efficacy for pursuing a career in medicine) nor the retention rate for URM individuals who do become scribes. Future studies might explore how and why a higher proportion of URM students are attracted to scribing than to medical school, and how to ensure retention of URM scribes.

Conclusion

This pilot study found that the vast majority of individuals working as medical scribes valued the experience for both the mentoring they received and the insights they gained about being a clinician. Recent research suggests that scribing positively impacts confidence in clinical note writing, history taking, medical knowledge, communication, and ability to function in the healthcare environment.33 It is therefore reasonable to imagine that scribing would provide URM premedical students with much-needed support in these areas and support them in their pursuit of medical education. Moreover, the present study indicates that the experiences of individuals from racial/ethnic groups that are under-represented in medicine did not differ from their majority counterparts, with almost 9 out of 10 respondents reporting that working as a scribe reinforced their commitment to pursue a career in medicine. If confirmed, these findings suggest that medical scribing may help increase diversity in medicine by providing a much-needed pipeline for recruiting under-represented minorities into medicine.

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was determined to be exempt from formal IRB review by the Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center (ID: 00015875)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to ScribeAmerica for their collaboration.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received for conducting this study or preparing this manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. We have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. ScribeAmerica played no role in conceptualizing this study, analyzing the data, or preparing this manuscript.

References

1. Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Affairs. 2002;21(5):90–102. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90

2. Stanford FC. The importance of diversity and inclusion in the healthcare workforce. J National Med Assoc. 2020;112(3):247–249. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2020.03.014

3. Pittman P, Chen C, Erikson C, et al. Health workforce for health equity. Med Care. 2021;59(10 Suppl 5):S405–S408. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001609

4. Mitchell K, Iheanacho F, Washington J, Lee M. Addressing health disparities in Delaware by diversifying the next generation of Delaware’s physicians. Delaware J Public Health. 2020;6(3):26. doi:10.32481/djph.2020.08.008

5. Garcia AN, Kuo T, Arangua L, Pérez-Stable EJ. Factors associated with medical school graduates’ intention to work with underserved populations: policy implications for advancing workforce diversity. Acad Med. 2018;93(1):82. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001917

6. Hadinger MA. Underrepresented minorities in medical school admissions: a qualitative study. Teaching Learning Med. 2017;29(1):31–41. doi:10.1080/10401334.2016.1220861

7. Poole KG Jr, Jordan BL, Bostwick JM. Mission drift: are medical school admissions committees missing the mark on diversity? Acad Med. 2020;95(3):357–360. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003006

8. Freeman BK, Landry A, Trevino R, Grande D, Shea JA. Understanding the leaky pipeline: perceived barriers to pursuing a career in medicine or dentistry among underrepresented-in-medicine undergraduate students. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):987–993. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001020

9. Mendoza FS, Walker LR, Stoll BJ, et al. Diversity and inclusion training in pediatric departments. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):707–713. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1653

10. Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, et al. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):117–140. doi:10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4

11. Takeshita J, Wang S, Loren AW, et al. Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(11):e2024583–e2024583. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24583

12. Greenwood BN, Carnahan S, Huang L. Patient–physician gender concordance and increased mortality among female heart attack patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(34):8569–8574. doi:10.1073/pnas.1800097115

13. Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A. Physician–patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(35):21194–21200. doi:10.1073/pnas.1913405117

14. Ma A, Sanchez A, Ma M. The impact of patient-provider race/ethnicity concordance on provider visits: updated evidence from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. 2019;6(5):1011–1020. doi:10.1007/s40615-019-00602-y

15. Jetty A, Jabbarpour Y, Pollack J, Huerto R, Woo S, Petterson S. Patient-physician racial concordance associated with improved healthcare use and lower healthcare expenditures in minority populations. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. 2022;9(1):68–81. doi:10.1007/s40615-020-00930-4

16. Alsan M, Garrick O, Granziani G. Does diversity matter for health? Experimental evidence from Oakland. Am Econ Rev. 2019;109(12):4071–4111. doi:10.1257/aer.20181446

17. Salsberg E, Richwine C, Westergaard S, et al. Estimation and comparison of current and future racial/ethnic representation in the U.S. health care workforce. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(3):e213789–e213789. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3789

18. Mora H, Obayemi A, Holcomb K, Hinson M. The national deficit of black and Hispanic physicians in the U.S. and projected estimates of time to correction. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(6):e2215485–e2215485. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.15485

19. Lett E, Murdock HM, Orji WU, Aysola J, Sebro R. Trends in racial/ethnic representation among U.S. medical students. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(9):e1910490–e1910490. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10490

20. Barr DA, Gonzalez ME, Wanat SF. The leaky pipeline: factors associated with early decline in interest in premedical studies among underrepresented minority undergraduate students. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):503–511. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816bda16

21. Gesner E, Gazarian P, Dykes P. The burden and burnout in documenting patient care: An integrative literature review. Vol. 264. MEDINFO 2019: Health and Wellbeing e-Networks for All. 2019. 1194–1198.

22. Downing NL, Bates DW, Longhurst CA. Physician burnout in the electronic health record era: are we ignoring the real cause? Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(1):50–51. doi:10.7326/M18-0139

23. Eley RM, Allen BR. Medical scribes in the Emergency Department: the scribes’ point of view. Ochsner J. 2019;19(4):319–328. doi:10.31486/toj.18.0176

24. Hewlett WH, Woleben CM, Alford J, Santen SA, Buckley P, Feldman M. Impact of scribe experience on undergraduate medical education. Med Sci Educator. 2020;30(4):1363–1366. doi:10.1007/s40670-020-01055-3

25. Abdulahad D, Ekpa N, Baker E, et al. Being a medical scribe: good preparation for becoming a doctor. Med Sci Educator. 2020;30(1):569–572. doi:10.1007/s40670-020-00937-w

26. Lin S, Duong A, Nguyen C, Teng V. Five years’ experience with a medical scribe fellowship: shaping future health professions students while addressing provider burnout. Acad Med. 2020;96(5):671–679. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003757

27. Odom KL, Roberts LM, Johnson RL, Cooper LA. Exploring obstacles to and opportunities for professional success among ethnic minority medical students. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):146–153. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d8f2c

28. Ehie O, Muse I, Hill L, Bastien A. Professionalism: microaggression in the healthcare setting. Curr Opinion Anaesthesiol. 2021;34(2):131. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000000966

29. Wong G, Derthick AO, David E, Saw A, Okazaki S. The what, the why, and the how: a review of racial microaggressions research in psychology. Race Social Problems. 2014;6(2):181–200. doi:10.1007/s12552-013-9107-9

30. AAMC. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. AAMC. Diversity and Inclusion Web site; 2019.

31. Bustraan J, Dijkhuizen K, Velthuis S, et al. Why do trainees leave hospital-based specialty training? A nationwide survey study investigating factors involved in attrition and subsequent career choices in the Netherlands. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e028631. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028631

32. Squiers JJ, Lobdell KW, Fann JI, DiMaio JM. Physician burnout: are we treating the symptoms instead of the disease? Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(4):1117–1122. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.08.009

33. Skelly KS, Weerasinghe S, Daly JM, Rosenbaum ME. Impact of medical scribe experiences on subsequent medical student learning. Med Sci Educator. 2021;31(3):1149–1156. doi:10.1007/s40670-021-01291-1

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.